PART TWO

FROM JUBAL' TO BORUS'S HARP

I.

THE HARP IN THE BIBLE

“The cherubic

host in thousand quires

Touch their immortal harps of golden wires”.

—Milton.

Jubal’s harp. Egyptian influence. The kinnor and nebel.

The harp associated with prophesying. Harps in Solomon’s Temple.

Jewish instruments. The New Jerusalem. Early Christian worship.

Music school at Rome under St. Leo.

The “music of the spheres”, as understood by the pagan

philosophers, finds its analogue in that beautiful passage from

the Book of Job, wherein we read that “the morning stars sang together, and

all the sons of God shouted for joy”. In the fourth chapter of the

Book of Genesis it is stated that Jubal, son of Lamech (seventh

in descent from, yet contemporaneous with, Adam), was “the father

of them that play upon the harp (kinnor) and the organ (ugab)”.

Whilst the Lutheran version reads “fiddlers and pipers”, the Revised

Version more correctly gives “harp and pipe”.

About the year B.C. 1730 there is mention made of serenading

distinguished visitors “with joy, and with songs, and with timbrels

(toph), and with harps (kinnor)”, as is recorded in Genesis (xxx.

27). The kinnor (said to have been the prototype of the trigon

or trigonon) has been equated with cithara or harp, and had from

eight to ten strings, resembling the Irish cruit, or ocht-tedach.

Although Josephus says that the kinnor was played with a plectrum,

the Bible credits David with playing on it “with his hand” (1 Kings

xvi. 23). One of the most pathetic passages in the Old Testament

is the description of the Israelites by the waters of Babylon hanging

their harps on the willow-trees. They could not tune their kinnors,

nor could they sing the songs of Israel in a strange land.

Some authorities equate the nebel, or nebelazor, of the

Bible with a form of harp, but it is more probable that it was a

psaltery. At the same time, it is only right to add that strong

arguments have been adduced to prove the nebel to have been a large

form of the kinnor, somewhat like the clairseach.

De Sola gives us what purports to be the veritable melody

which was sung by Miriam and her companions (Exodus xv. 21,

22), but it is agreed by most scholars that this antiphon, rendered

as it was by two millions of voices in unison, to the accompaniment

of timbrels and dances, was more or less an adaptation of Egyptian

music.

It is natural to suppose that the intercourse for four

hundred years in Egypt materially influenced the music of the Israelites. Music

in Egypt was so intimately bound up with the temple that it was

almost exclusively a sacred art, for, as is testified by Ranke,

religion dominated over all, and there was little of the secular

element permitted. Presided over by the priests, the sacred songs

and melodies were most jealously guarded, and no innovations were

allowed, as can be gathered from Plato. However, the wanderings

of the Children of Israel through the desert, and the succeeding

five hundred years of strife with neighbouring nations, left the

chosen people in a rather primitive condition as regards music.

There seems to have been a most intimate connection between

the harp and the gift of prophecy. We read that the company of prophets whom

Saul met “coming down from the high place with a psaltery,

and a timbrel, and a pipe, and a harp before them”, were found prophesying;

and that Saul himself, smitten with the same spirit, prophesied

among them (1 Kings x. 5-10). Again, the prophet Elias, fairly excited

with holy zeal, ordered a musician to be brought to calm his soul;

and “when the minstrel played, the hand of the Lord came upon him,

and he obtained favours in abundance” (4 Kings III. 13-15). The

royal prophet, too, illustrates the intimate connection between

music and prophecy when he says, “I will open my dark saying upon

the harp” (Psalms XLIX. 4).

David, before his death, gave the most minute directions

to Solomon regarding the building of the Temple and its adornment,

with special reference to the musical arrangements. He himself is

known to have played on the psaltery and the harp.

In Solomon’s Temple the music was on a most colossal

scale, and even the Albert Hall choirs pale into insignificance before the monster

choral services associated with this glorious building. Foreign

workmen were employed for the finer and more delicate portions,

as well as to make special instruments: “And the King made of the

thyme trees [almug-tress, or sandal-wood] the rails of the house

of the Lord, and of the King’s house, and citterns and harps for

singers” (3 Kings x. 12). It almost reads like a legend what

is told of the Temple services, and of the 200,000 priests, with

trumpets, and 40,000 harps and psalteries. Not only were there

4000 Levites to sing praises to the Lord with instrumental accompaniment,

but we read that there were 288 trained singers, who sang beside

the altar to the harp and other instruments.

The dedication of the wall of Jerusalem took place, as

Nehemiah tells us, “with singing, and with cymbals and psalteries

and harps”. In fact, music was as essential to religious celebrations

with the Jews as with the Egyptians. But,

alas! very little is actually known of even the shape of the Jewish

instruments, as not a single bas-relief exists by which we can accurately

judge. We can only assume that the Hebrews used the same instruments

as the Egyptians and Assyrians and Chaldeans, from whom they derived

their musical system. Herod rebuilt the Temple, B.C. 25, but it

was utterly razed under Titus, when the harp was ever after silent.

In the Book of Revelation St. John tells us that the

mighty choral praise of the elect in the New Jerusalem will have

a grand accompaniment of multitudinous harps, for ever proclaiming

the greatness of Him whose mercy endureth for ever

For the first four centuries of the Christian era there

could have been no ornate musical services, owing to the persecutions.

It is now agreed that the early Christian music was an amalgam of

simple melodies with the adapted psalmody and sacred songs from

the Temple of Jerusalem. It is reasonable to believe that the harp

was for a time used by the converted Jews, as it was the policy

of the early Church to allow a free hand in matters of discipline,

and, of course, the traditions of the Temple were very dear, especially

the antiphonal chanting of the psalms. Greek-art, of necessity,

was a factor in the liturgic chants, as also Roman art, and so the

evolution of sacred music proceeded, culminating in the foundation

of a music school at Rome, by Pope St. Leo, in the year 460.

In the orchestra sculptured in high relief in the Portico della Gloria of Santiago de Compostela,

in Spain, there are twenty-four life-size figures, representing

the twenty-four elders seen by St. John in the Apocalypse. As these

figures were executed in 1188 (as stated on the inscribed lintel),

they are specially interesting, and there are harps, psalteries,

cruits, and viols in evidence.

| PORTICO

DE LA GLORIA |

|

II.

THE IRISH HARP

Singing to the harp in ancient Ireland. The last Feis

of Tara. St. Columcille. The ceis. Clarisech and fidil in the seventh

century. Irish monasteries in England. “Glastonbury of the Irish”.

Sculptured Irish harps of the ninth century. A band of harps. The

Irish monks of St. Gall. Alfred the Great. St. Dunstan’s Aeolian

harp. Ilbrechtach the Harper.

As early as the sixth century Irish ecclesiastics were

wont to sing psalms and hymns to the accompaniment of the cruit

or small harp. This custom continued for seven centuries, as Giraldus

Cambrensis (as late as 1190) tells of the bishops and abbots “who

travelled about with their harps”, utilising their instrumental

powers as a means of gaining converts. Giraldus also alludes to

St. Kevin’s (sixth century) harp.

In the same century we read of a famous Feis (gathering)

at which over a thousand bards were present. All readers have heard

of “Tara’s halls”, but it is not as generally known that the great

Feis, or Parliament of Tara, was held triennially (O'Donovan says

septennially) by the chief monarch of Ireland. The Feis of

Tara, Co. Meath, was a representative assemblage of the men of Erin,

who met on the third day before the feast of Samhain—the first of

November—and ended the third day after it. When the business of

each day was concluded there was minstrelsy in the banquet hall.

The last Feis of Tara was in 560, under the presidency of Dermot

mac Fergus, Head King of Ireland, the founder of Clonmacnoise. In

that year it was cursed by St. Ruadhan of Lorrha, and never more

was the harp heard in Tara’s halls.

There is an interesting reference to the cruit in the

Life of St. Columcille, by St. Eunan (Adamnan),

as follows: — “On one occasion as St. Columcille

was seated with some disciples on the banks of Loch Cé [near Boyle,

Co. Roscommon], a bard came up to him and entered into conversation

with the little band of monks. When the poet-minstrel had departed,

the disciples of St. Columcille asked: '’Why did you not ask the

bard Cronan to sing a song for us to the accompaniment of his harp

[cruit], as poets are wont to do?’.”

In an ancient eulogy of St. Columcille, who died in 596,

we read of a “song of the cruit without the ceis”; that is, a harp-melody

without the harp-fastener (ceis), or an air played on an untuned

harp. About this time the cruit had a formidable rival in a larger

form of harp called the clairsech, the festive or heroic harp of

mediaeval Erin.

For centuries the general name of the harp in Ireland

has been clairsech, and the Irish brought the instrument to Scotland

at the close of the sixth century, where it has ever since been

known by the same name. It is remarkable that the parent

of the modern violin also hails from Ireland. Certain it is that

the fidil, or fiddle, is alluded to in an authentic Irish manuscript

of the seventh century, known as the “Fair of Carman”. Fidil, in

Irish, means a little bent rod, or bow, from the root fid=a rod,

and the instrument was certainly in use in Ireland in 650—that is,

two hundred years before the time of Ottfried von Weissenburg, O.S.B.

The Annals of Ulster, under date of the year 634, chronicle

the death of Ailill the Harper, son of Aedh Slaine, Ard Righ (Head

King) of Ireland. Other entries during the same century point to

the popularity of the cruit, the clairsech, and the timpan, as also

the fidil. According to an Irish saga of the seventh century, nine

Irish harpers are described as having “grey winding cloaks, with

brooches of gold, circlets of pearls round their heads, rings of

gold around their thumbs, torques of gold around their ears, torques

of silver around their throats”, etc.

It is tolerably certain that the Irish missionaries of

the fifth and sixth centuries introduced the harp into England.

Lindisfarne, Ripon, Durham, Lichfield, Tilbury, Dunwich, Burgcastle,

Bosham, etc., were all Irish foundations. St. Mailduff was a skilled

harper, and he was succeeded as Abbot of Mailduffsburgh (Malmesbury)

by his pupil, St. Aldhelm, in 675, who was also a performer on the

harp.

The great monastery of Glastonbury was known as “Glastonbury

of the Irish”, and Ina, King of the West Saxons, in 709, endowed the

monastic church at the suggestion of St. Aldhelm, then Bishop of

Sherborne. No stronger confirmation of the Irish origin of

Glastonbury need be cited than the dedication of the abbey church

to St. Mary and St. Patrick, whilst a chapel was dedicated to St.

Brigid. St. Dunstan’s biographer says that the future Archbishop

of Canterbury was so learned in all the arts and sciences that his

enemies advanced the plea that “he had been trained to necromancy

by his Irish teachers in the island of Avalon”.

Irrespective of the Ullard Harp (circ. 845), there are

half-a-dozen harps sculptured on the magnificent high crosses of

Ireland, dating from the years 860-990. They are reproduced

in Colonel Sculptured Wood-Martin’s Pagan Ireland, and in Miss Stokes’s

High Crosses of Castledermot and Durrow. One of the figures on the

Durrow Cross is playing on a six-stringed cruit, with a bridge and

a bow. This, as has previously been stated, was a developed stage

of the cruit, as the distinctive Irish instrument of that name,

popular in pagan and early Christian days, was only in size from

twenty to thirty inches, and easily carried about, being generally

attached to the girdle of the performer.

At the close of the seventh century there is unquestionable

evidence as to performances by a “band of harps”. Dalian Forgaill,

in his Amra, or Elegy, on St. Columcille, alludes to “the small

harp which is used as an accompaniment to a large harp in concerted

playing”. The term cómseinm, derived from cóm = together, and

seinm = playing, can only be understood of a band of harps, or an

instrumental combination of harps. This explanation is fully brought

out by Stokes in the Revue Celtique (xx. 165). Nor is it so surprising

that the Irish of the eighth century had a band of harps, because,

as Professor Wooldridge admits, in the Oxford History of Music,

they were then so advanced in the art of music that they were fully

acquainted with the free organum of the fourth, or of the diatesseron.

In fact, John Scotus Erigina, the Irish philosopher, is the first

to allude to discant or organum, in 860. This he does in his tract

De Divisione Naturae.

FIG. 13.—TRIANGULAR

SAXON

HARP (ninth century). |

|

Many of the Irish monks of St. Gall were skilled harpers,

and it is on record that Tuathal (Tutilo), head-master of the music

school at that famous abbey, delighted in the cruit and the psaltery.

Many of his compositions have survived—including “Hodie Cantandus”

and “Omnipotens Genitor”, as we learn from Schubiger. He died in

extreme old age, on April 27th, 915.

The Anglo-Saxons were not slow to cultivate the Irish

cruit, which, as we have seen, was called hearpe by them. St. Bede

attests the popularity of this instrument in his time, and that

it was a custom to pass it from one to another at all feasts. The

beautiful drawing of a cruit in a tenth-century manuscript in the

British Museum (Vitellius, F. XI.) is of Irish origin, as Professor

Westwood admits, and is styled “an Irish crotta”, by Carl Engel.

All readers of English history are familiar with the story of Alfred

the Great (871-901) and his disguise as a harper whilst in the Isle

of Athelney. Even assuming that the story is mythical, the harp

must have been very popular with the Anglo-Saxons.

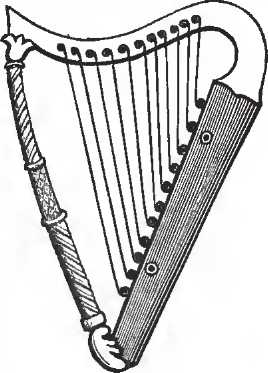

fig. 14.—HARP OF

NINTH

CENTURY. |

|

St. Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury (d. 988), stands

out pre-eminently in connection with the harp. Even allowing for

the traditional romance attaching to his history, St. Dunstan must

have been a proficient on the hearpe. The charge of sorcery brought

against him was owing to the his Aeolian harp :—

“By the desultory breeze caressed

It pours forth sweet upbraiding”.

His biographer tells us that the saint placed his harp

in a certain position, with the result that the wind, as it wafted

along the strings, caused the most delightful music. Nor are we

left to mere references as regards the cultivation of the harp in

pre-Norman days. In the British Museum and the University Library

of Cambridge, there are illustrations of tenth-century harps.

Among the distinguished Irish bards of the tenth century,

Flann mac Lonain was celebrated, and some of his poems are still

preserved; in one of which he describes a harper called Ilbrechtach,

of Slieve Aughty, near Kinalehin, Co. Galway. This harper is said

to have travelled with Mac Liag, the poet and historiographer of

Brian Boru, who was incensed at the minstrel’s praise of his predecessor

Mac Lonain.

Let us now turn our attention to Wales, which claims

a chapter all to itself.

III.

THE WELSH HARP

Ancient “British”music. “Morva Rhuddlan”. The Telyn,

or Welsh harp. Derivation of name. Eisteddfodau in the twelfth century.

Giraldus Cambrensis. The name Telyn used in Brittany and Cornwall.

Compass of early Welsh harps. The crwth trithant. Tunings of the

crwth.

From the third to the tenth century there was constant

intercourse between Wales and Ireland. Irish immigrants popularised

Celtic minstrelsy and developed a love of music among the Welsh.

Warton in his History of English Poetry says:—“There is sufficient

evidence to prove that the Welsh bards were early connected with

the Irish. Even so late as the eleventh century the practice continued

among the Welsh bards of receiving instruction in the bardic profession

(music and poetry) from Ireland”.

We can dismiss as quasi-fabulous the legends of the pre-Christian

Welsh harpers, and the “British” songs sung at the Court of King

Arthur, etc. The credulity of eighteenth century Welsh writers as

to some of their melodies going back to the sixth or seventh century

is simply marvellous. For example, the melody known as “Morva

Rhuddlan”, said to have been composed by the bard of Caradoc, after

the battle of Rhuddlan in 795, is an Irish air of the seventeenth

century, adapted by Moore to “Avenging and Bright”.

We have previously treated of the Welsh crwth, quite

a different instrument from the Irish cruit. One of the earliest

references to the crwth is in the Anomalous Laws, dating from the

twelfth or century, but the typical harp of Wales was known as the

Telyn. In all authentic Welsh documents the harp is invariably given

under the name Telyn. O'Curry derives this name from the buzzing

sound of the hair-strung harp. From the Welsh laws it appears that

the ordinary or lower-grade harpers of Wales in the twelfth century

were wont to play on harps strung with horse-hair, and that the

chief harper was entitled to a fine of twenty-four pence from each

minstrel who exchanged his hair-strung harp (telyn) for a gut-string

one.

Several entries in the Irish annals—from 950 to 1090—testify

to the exodus of Irish harpers to Wales, whilst it is absolutely

certain that Griffith ap Cynan was born of an Irish mother in Ireland

in 1065. At the Eisteddfod of Caerwys, in 1100, Welsh music

was codified under the direction of Malachy the Gwyddilian (the

Irishman), and twenty-four musical canons were adopted. One most

convincing fact adduced by Bunting, in 1809, is that the names

of the twenty-four measures of Welsh music, said to date from the

time of Prince Griffith ap Cynan, are written in Irish—a fact hinted

at by Jones.

In Dowling’s Annals of Ireland is recorded the death

of Prince Griffith, in 1137. It is said of him that “he led back

with him from Ireland harps, timpans, cruits, cytharae, and harpers”.

His son, Cadwallader ap Griffith, also went over to Ireland, and

brought back with him harpers.

Following on the Eisteddfod at Caerwys (1100), there

was another held by Cadogan, Prince of Powis, in the Castle of Cardigan,

at Christmastide of the year 1107. Of the successive meetings during half a century,

there are but scant particulars. However, in 1176, a famous Eisteddfod,

somewhat on the lines of the Irish Feis, was celebrated in Cardigan

Castle by Rhys ap Griffith, when harp competitions were a feature.

Giraldus Cambrensis, in the twelfth century, writes as

follows:—“Scotland and Wales, the former by reason of her derivation,

the latter from intercourse and affinity, seek with emulous endeavours

to imitate Ireland in music”. It is very remarkable that Giraldus

Cambrensis does not refer to the Welsh crwth in his enumeration

of instruments, though he notices its counterpart, the timpan, in

Ireland. His account makes it certain that the telyn and the cruit

were identical. He also adds that “the Irish were wont to use brass

wires for their harps in preference to those of gut”, implying,

of course, that his own Welsh harp had hair or gut. It is interesting,

too, to note that the Britons also call the harp telyn, as likewise

do the Cornish.

Again, as a further proof of the Irish origin of the

Welsh harp, we learn from Pennant that the telyn was a small instrument,

with only nine strings, Compass and only one row. He adds

that the single row of strings continued till after the Middle Ages,

when a double row succeeded. The learned Selden, in his notes to

Drayton’s Polyolbion, agrees to the view that Wales derived her

minstrelsy from Ireland. In the fourteenth century, when the

Irish clairsech, or large harp, was all the fashion, the Welsh harps

were made on the same lines. Jones describes a sixteenth-century

“Welsh” harp which had only one row of thirty-three strings, and

measured four feet nine inches in height; but, a Bunting observes,

it may well be called an “Irish” harp, to which, he assures us,

“it exactly answers in size and number of strings”.

Thus, Wales, as late as the fourteenth century, had no

distinctive harp save the telyn, which was in reality an Irish harp. The

older crwth, similar to the Irish cruit, was at this date transformed

into the instrument as described by the Hon. Daines Barrington,

in 1776, which he heard played by John Morgan in the Isle of Anglesey. What

was known as the crwth trithant, as pictured in manuscripts

of the eleventh century, was merely the three-stringed lyre. The

post-Reformation crwth was played as late as 1801, as stated by

Bingley in 1814, but we are in the dark as to the exact method of

tuning it.

According to Edward Jones (1752-1824), the later form

of crwth was tuned as follows:—

Tunings of the Crwth

He explains that the two outlying strings, plucked with

the thumb of the left hand, were G and g, while the four strings

on the finger-board, and played with the bow, were tuned c to C

and D to d, as printed above.

In size, the crwth was from 20 to 22’1/2 inches long,

the width being from 10 inches at the tail-piece to 8’1/2 inches

at the top, and the height of the sides two inches. The sound-holes

were round, having a diameter of a little over an inch. Bunting

says that the sculptured harp in Melrose Abbey (Scotland), dating

from the fourteenth century, is probably a crwth. For further information

as to the eighteenth-century crwth the reader is referred to Carl

Engel’s treatise, of which an excellent summary is given by Mr.

Paul Stoeving, in his Story of the Violin.

At the close of the fourteenth century the minstrels

helped to fan the spirit of resistance to English rule, and so powerful

were they in 1402 that an enactment was passed forbidding any one

to maintain rimers or minstrels.

IV.

“BRIAN BORU’S” HARP

Outline of the ‘Brian Boru’ legend. Examination of claims

in the light of history. Description of the O'Brien harp. Clue to

the real story. Probable date. Its wanderings. Restrung in the eighteenth

century. Presented to Trinity College, Dublin. Cast of it in South

Kensington Museum.

Brian Boru’s harp |

|

All visitors to Trinity College, Dublin, are shown Brian

Boru’s harp, it being supposed that this venerable instrument really

belonged to King Brian the hero of Clontarf. Perhaps it may be necessary

to explain that Brian Boru, recte Brian Borumha, was supreme monarch

of Ireland from 1003 to 1014. On April 23rd, 1014, he gave an overwhelming

defeat to the Danes at Clontarf, near Dublin, but was, unfortunately,

slain in the hour of victory. His harp and jewels were, as the story

goes, taken by his son Donogh, who, however, did not succeed to

the sovereignty of Ireland, Malachi, the former monarch, having

resumed the government.

Donogh O'Brien, after Clontarf, returned to his palace

at Kincora, but his right to the kingship of Thomond was disputed

by his elder brother, Tadhg. For years a fratricidal war continued,

which only ended with the death of Tadhg in 1023, whereupon Donogh

was acknowledged King of Munster. He had a troubled reign,

and at length was defeated, in 1061, at Slieve Crot, Co. Tipperary,

by Dermot mac Maelnambo, King of Leinster. After this, misfortune

followed on misfortune, and, in 1062, King Donogh, then over seventy

years of age, made a pilgrimage to Rome, and presented his crown

and sceptre to Pope Alexander II. Not alone did Donogh O'Brien (whose

wife was Driella, sister of Harold II, King of England) bring his

father’s crown andregalia to Rome, but, as is said, also brought

his father’s harp, which he bequeathed to the Pope. Anyhow, he died,

“after the victory of penance”, at the monastery of St. Stephen,

in Rome, in 1064, and the harp is said to have remained as one of

the treasures of the Vatican till 1521. In the latter year it was

given by Pope Leo X to King Henry VIII of England, at the same time

that the Pontiff conferred on the English monarch the title “Fidei

Defensor” (F.D. = Defender of the Faith), in recognition of his

Defence of the Seven Sacraments. Finally, in 1543, when Henry VIII

conferred the title of Earl of Clanrickarde on Mac William (Ulick)

de Burgo, he presented the Earl with this Irish harp, said to have

belonged to Brian Borumha. Vallancey says that the harp, after a

time, reverted to O'Brien, Earl of Thomond, and eventually became

the property of Ralph Ouseley of Limerick.

The above is a summary of the story as generally told;

but there is another version, written by Ralph Ouseley above mentioned,

dated October 22nd, 1783, to be found among the Egerton Manuscripts

in the British Museum:—

“This harp lay in the Vatican till Innocent XL, in 1678,

sent it as a token of his goodwill to Charles II, who had it deposited

in the Tower. Soon after this, the Earl of Clanrickarde, seeing it

among the curiosities, mentioned to the King that he knew an Irish

nobleman that Lwould probably give a limb of his estate for it (meaning

the Earl of Thomond), on which his Majesty immediately replied:

‘I make you a present of it; dispose of it as you please’. Lord

Clanrickarde brought it to Ireland, and Lord Thomond, being on his

travels, never was possessed of it. Some years after, it was purchased

by Lady Huxley for twenty rams and as many swine of English breed,

and bestowed by her on her son-in-law, Henry MacMahon of Clenagh,

in the County of Clare, who, about the year 1756, bestowed it to

Matt. MacNamara, of Limerick, Esq., Counsellor-at-Law, and some

years Recorder of that city, a most worthy, honoured, polite, and

hospitable gentleman. When given to Counsellor MacNamara, it had

silver strings and some more ornaments of plate than are now to

be seen; they were stolen or destroyed by the servants, or idle

people fiddling withal, as was also a letter from Mr. MacMahon,

giving a full and particular history of the said harp. It was left

as a token of esteem by Counsellor MacNamara, who died in 1774,

to Ralph Ouseley, of Dublin, an admirer of antiquity, and by him

presented, in 1781, to the Right Hon. W. Conyngham, whose taste

for the fine arts . . . deserves the highest encomiums”.

The latter account looks very circumstantial, but the

only part that can be accepted without hesitation is the history

of the instrument from about the year1720, when it came into the

possession of Henry MacMahon. Let us now briefly examine the claims.

We may at once state that an examination of the harp itself is conclusive

as against the supposed date of 1014. The workmanship is thirteenth

century, though Petrie inclined to the view that it was not made

before the second half of the fourteenth century.

There is no documentary evidence that Donogh

O'Brien brought any harp with him to Rome; nor yet has any one of

the Irish annalists alluded to King Brian Borumha as a harpist,

although they do tell us that he was a skilled chess-player. Again,

there is no proof that Pope Innocent XI, in 1678, sent any Irish

harp to King Charles II. Here let us give Dr. Petrie’s admirable

description of the Brian Boru’s harp:—

“From recent [1838] examination, it appears that this

harp had but one row of strings; that these were 30 in number, not

28, as was formerly supposed, 30 being the number of brass tuning-pins

and of corresponding string-holes. It is 32 inches high, and

of exquisite workmanship; the upright pillar is of oak, and the

sound-board of red sallow; the extremity of the fore-arm, or harmonic

curved bar, is capped in part with silver, extremely well wrought

and chiselled. It also contains a large crystal set in silver, under

which was another stone, now lost. The buttons [bosses], or ornamental

knobs, at the side of the curved bar are of silver. The string-holes

of the sound-board are neatly ornamented with escutcheons of bears

[? lions] carved and gilt. The four sounding-holes have also had

ornaments, probably of silver, as they have been the object of theft.

The bottom which it rests upon is a little broken, and the wood

very much decayed. The whole bears evidence of having been the work

of a very expert artist”.

Before adding any comment on this excellent description,

it may be well to quote an incident of the year 1216, which furnishes

a clue to the real origin of the Brian Boru harp.

In 1216 Finn O'Bradley, steward of the Prince of Tyrconnell

(Donal mor O'Donnell), was sent to collect tribute, but was slain,

in a fit of anger, by Muiredach O'Daly of Lisadil, Co. Sligo, a

famous Irish minstrel, who fled to Scotland, where he remained from

1217 to 1222. Whilst in Scotland, he wrote three celebrated

poems to O'Donnell, who allowed him to return to his native country,

and took him back into friendship. Meantime, Donnohadh Caribre O'Brien,

King of Thomond, sent his own harp—“the jewel of the O'Briens”—as

a pledge to Scotland for the ransom of the bard O'Daly. Accordingly,

the Irish minstrel was allowed to return home, but the harp was

detained in Scotland, where it remained for over eighty years.

Thus we can trace the history of a rare harp of the O'Briens,

sent to Scotland about the year 1221, as a pledge, by the valiant

King of Thomond, whose death took place on March 8th, 1243.

O'Daly’s Irish poems are preserved in Scotland in the

Dean of Lismore’s Book, the editor of which work says that O'Daly

“was the ancestor of the MacVurricks, bards to the MacDonalds of

Clanranald”—the bard himself being known in Ireland as albanach—that

is, “the Scotchman”—from his seven years’ residence in Scotland.

The O'Brien harp may fairly be dated as from about the

year 1220, and it was sent to Scotland in 1222. In 1228 or 1229,

Gillabride MacConmidhe, a famous Ulster bard, was commissioned by King

O'Brien to endeavour to ransom the much-prized instrument. In

response to this request, the bard composed the well-known “Ransom

Song”, but, alas! the lovely O'Brien harp would not be restored

for “whole flocks of sheep”, and so, as O'Curry remarks, it remained

in Scotland until King Edward I took it with him to Westminster

in 1307.

It lay at Westminster from 1307 until July 1st, 1543,

when Henry VIII presented it to the first Earl of Clanrickarde,

who, at his death in 1547, bequeathed it to his son Richard,

second Earl, husband of Margaret, daughter of O'Brien, Earl of Thomond.

Thus the harp reverted to its old owners about the middle of the

sixteenth century, as Lady Clanrickarde presented it to Conor, Earl

of Thomond.

In 1570 there was an Irish poem written in praise of

the “O'Brien Harp”, which had, during the enforced absence of its

owner, Conor, Earl of Thomond, been in temporary possession of a

certain O'Gilligan, a famous harper. The Irish bard describes it

as “a musical, fine-pointed [curved], speckled [ornamented] harp”,

and it is added: “though sweet in the hands of O'Gilligan, it was

sweeter far in the halls of O'Brien”.

By intermarriage, we find the O'Brien Harp in possession

of Henry MacMahon of Clenagh, Co. Clare, in 1750,. who, in 1756,

presented it to Matthew MacNamara, Recorder of Limerick.

Arthur O'Neill, the harpist, tells us that when he visited

Limerick in 1760, he had the honour of playing on the Brian Boru

harp, restored for the occasion at the cost of Mr. MacNamara. On

the death of the latter gentleman in 1774, the harp was bequeathed

to Ralph Ouseley, a musical amateur (grandfather of Sir Frederick

Gore Ouseley, Bart., Mus. Doc), and a noted antiquarian, who, in

1781, as before stated, presented it to the Right Hon. William Burton

Conyngham, P.C

Conyngham (who died in 1796) presented the O'Brien Harp

to Trinity College, where it has ever since remained. When

deposited in the College Museum it was in a deplorable condition,

as the harmonic curved bar was broken and fastened over the sound-box. Dr.

Robert Ball made a very careful restoration of the Dublin instrument,

supplying the lost portions from analogy, and lent it “as the oldest

known specimen of Irish harp” to the committee of the Dublin Exhibition,

in 1853.

| TRINITY COLLEGE HARP |

|

Curiously enough, one of the escutcheons, or silvered-bronze

badges, which Petrie describes as having been stolen, was found

in the Phoenix Park, Dublin, in 1876. From the armorial bearings

Petrie was led to believe that the harp belonged to an ecclesiastic

of the O'Neill family, and he dated the instrument as from the close

of the fourteenth century, but O'Curry’s view is convincing in favour

of the harp having belonged to Donnchadh Caribre O'Brien, King of

Thomond, in 1218.

Although the original harp of O'Brien is in the Library

of Trinity College, Dublin, there, is a good cast of it in the South

Kensington Museum, and a description of it is furnished by Carl

Engel in his admirable Catalogue. However, by far the most accurate

drawings of this Museum venerable instrument will be found in Mr.

R. Bruce Armstrong’s magnificent monograph on the Irish and Highland

Harps, a sumptuous quarto, issued in 1904, but now withdrawn from

circulation. Only 180 copies were printed. Mr. Armstrong enters

into the most minute particulars as to the harp itself and its Irish

ornamentation.