|

THEHISTORY OF MUSIC LIBRARY |

|

THE VIOLIN. ITS FAMOUS MAKERS AND THEIR IMITATORSBY GEORGE HART SECTION VII The Violin and its Votaries Sterne (himself a

votary of the Fiddle) has well said, "Have not the wisest of

men in all ages, not excepting Solomon himself, had their hobby-horses—their

running-horses, their coins and their cockle-shells, their drums

and their trumpets, their Fiddles, their pallets, their maggots

and their butterflies? And so long as a man rides his hobby-horse

peaceably and quietly along the king's highway, and neither compels

you nor me to get up behind him,—pray, sir, what have either

you or I to do with it?" He further tell us, "There is

no disputing against hobby-horses;" and adds, "I seldom

do: nor could I, with any sort of grace, had I been an enemy to

them at the bottom; happening at certain intervals and changes of

the moon, to be both Fiddler and painter."

The leading instrument

is singularly favoured. It may be said to have a double existence.

In addition to its manifold capabilities, it has its life of activity

on the one hand, and inactivity on the other. At one time it is

cherished for its powers of giving pleasure to the ear, at another

for the gratification it affords to the eye. Sometimes it is happily

called upon to perform its double part—giving delight to both

senses. When this is so, its existence is indeed a happy one. The

Violin thus occupies a different position from all other musical

instruments. Far more than any other musical instrument it enters

into the life of the player. It may almost be said to live and move

about with him; the treasure-house of his tenderest and deepest

emotions, the symbol of his own better self. Moreover, the Violin

is a curiosity as well as a mechanical contrivance. Thus it is cherished,

perhaps for its old associations—it may have been the companion

of a valued friend, or it may be prized as a piece of artistic work,

or it may be valued, independently of other associations, for the

simple purpose for which it was made, viz., to answer the will of

the player when touched with the bow. The singular powers centred

in the Violin have been beautifully expressed by Oliver Wendell

Holmes, who says: "Violins, too. The sweet old Amati! the divine

Stradivari! played on by ancient maestros until the bow hand lost

its power, and the flying fingers stiffened. Bequeathed to the passionate

young enthusiast, who made it whisper his hidden love, and cry his

inarticulate longings, and scream his untold agonies, and wail his

monotonous despair. Passed from his dying hand to the cold virtuoso,

who let it slumber in its case for a generation, till, when his

hoard was broken up, it came forth once more, and rode the stormy

symphonies of royal orchestras, beneath the rushing bow of their

lord and leader. Into lonely prisons with improvident artistes;

into convents from which arose, day and night, the holy hymns with

which its tones were blended; and back again to orgies, in which

it learned to howl and laugh as if a legion of devils were shut

up in it; then, again, to the gentle dilettante, who

calmed it down with easy melodies until it answered him softly as

in the days of the old maestros; and so given into our hands, its

pores all full of music, stained, like the meerschaum, through and

through with the concentrated hue and sweetness of all the harmonies

which have kindled and faded on its strings." The gifted author

of "The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table" has evidently

made himself acquainted with the various life-phases of a Violin. The fancy for the

Violin as a curiosity has been a matter of slow growth, and has

reached its present proportions solely from the intrinsic merits

of its object. The Violin has not come suddenly to occupy the attention

of the curious, like many things that might be named, which have

served to satisfy a taste for the collection of what is rare or

whimsical, and to which an artificial value has been imparted. In

those days when the old Brescian and Cremonese makers flourished,

the only consideration was the tone-producing quality of their instruments;

the Violin had not then taken its place among curiosities. The instruments

possessing the desired qualities were sought out until their scarcity

made them legitimate food for the curious. Beauties, hitherto passed

over, began to be appreciated, the various artistic points throughout

the work of each valued maker were noted, and in due time Violins

had their connoisseurs as well as their players. Besides Italy, England,

France, and Germany have had their great men in the Fiddle world,

whose instruments have ever been classed as objects of virtu.

Mace, in his "Musick's Monument," published in 1676, gives,

perhaps, the earliest instance of curiosity prices in England. "Your

best provision (and most compleat) will be a good chest of Viols;

six in number, viz., two Basses, two Tenors, and two Trebles, all

truly and proportionally suited; of such there are no better in

the world than those of Aldred, Jay, Smith; (yet the highest in

esteem are) Bolles and Ross (one Bass of Bolles I have known valued

at �100). These were old." From the above curious extract we

glean that the Fiddle family was receiving some attention. The makers

in England whose instruments seem to have reached curiosity prices

are Bolles, Jay, Barak Norman, Duke, Wamsley, Banks, and Forster:

the value attached at different periods to the works of these men

has nearly approached the prices of Cremonese work. Of course, the

high value set upon the instruments of the makers above named was

confined to England. Turning to France,

we find that many of the old French makers' instruments brought

prices greatly in excess of their original cost. The favourite French

makers were M�dard, Boquay, Pierray, of the old school, and Lupot

and Pique of the modern. In Germany there

have been makers whose works have brought very high prices. Stainer,

Albani, Widhalm, Scheinlein, are names that will serve to associate

high values with German work. In the case of Jacob Stainer, the

celebrity of his instruments was not confined to Germany; they were

highly prized by the English and French, and at one period were

more valued than the best Amatis. It was not until the vast superiority

of Italian Violins over all others was thoroughly recognised, that

the love of the instrument as a curiosity reached its present climax.

In Italy, the value set upon the chief Cremonese works, though great,

was comparatively insignificant, as far as the Italians themselves

are concerned, and when France and England came into competition

with them for the possession of their Violins by Amati, Stradivari,

Guarneri, and the gems of other makers, they at once yielded the

contest. The introduction

of Italian instruments into Great Britain was a matter of slow growth,

and did not assume any proportions worthy of notice until the commencement

of the present century, when London and Paris became the chief marts

from whence the rare works of the old Italians were distributed

over Europe. By this time the taste of the Fiddle world had undergone

a considerable change. The instruments in use among the dilettanti in

France and England had hitherto been those built on the German model

of the school of Jacob Stainer. The great German maker was copied

with but little intermission for upwards of a century, dating from

about 1700 to 1800, a period of such considerable extent as to evidence

the popularity of the model. Among the Germans who were following

in the footsteps of Stainer were the family of Kloz, Widhalm, Statelmann,

and others of less repute. In England there was quite an army of

Stainer-worshippers. There were Peter Wamsley, Barrett, Benjamin

Banks, the Forsters, Richard Duke, and a whole host of little men.

Among the makers mentioned there are three, viz., Banks, Forster,

and Richard Duke, who did not copy Stainer steadfastly. Their early

instruments are of the German form, but later they made many copies

of the Cremonese. To Benjamin Banks we are indebted for having led

the English makers to adopt the pattern of Amati. He had long laboured

to popularise the school which he so much loved, but met with little

encouragement in the beginning, so strong was the prejudice in favour

of the high model. However, he triumphed in the end, and completely

revolutionised the taste in England, till our Fiddle-fanciers became

total ab-Stainers! Then commenced the taste for instruments

of flat form. Where were they to be found? If the few by the early

English makers be excepted, there were none but those of the Italians

to be had, and perhaps a few old French specimens. Attention was

thus directed to the works of the Cremonese, and the year 1800 or

thereabouts may be put down as the time when the tide of Italian

Violins had fairly set in towards France and England. The instruments

by the Amati were those chiefly sought after; the amount of attention

they commanded at this period was probably about equal to that bestowed

upon the works of Stradivari and Guarneri at the present time. Violins

of Amati and other makers were, up to this time, obtainable at nominal

prices. The number in Italy was far in excess of her requirements,

the demand made upon them for choir purposes in former days had

ceased, and the number of Violins was thus quite out of proportion

to the players. The value of an Amati in England in 1799 and 1804

may be gathered from the following extracts from the day-book of

the second William Forster, who was a dealer as well as maker—"20th

April, 1799. A Violoncello by Nicholas Amati, with case and bow,

�17 17s. 0d.;" and further on—"5th July, 1804, an

Amati Violin �31 10s. 0d." These prices were probably less

than those which William Forster received for many instruments of

his own make. It is certain that these low prices did not long continue;

the price increased in due proportion to the vanishing properties

of the supply. The call for Violins by the Amati was so clamorous

as speedily to effect this result; the prices for them were doubled,

trebled, and often quadrupled, until they no longer found a home

in their native land. The value set on them by the French and English

so far exceeded that which the Italians themselves could afford,

even though inclined to indulge in such things, that the sellers

were as eager to sell as the buyers to buy. During the time of this

scramble for instruments of Cremona, the theory of the flat model

was fast gaining ground. The circulation of the works of Cremona

among the players of France and England led to a comparison of the

various forms, and it was found that the elevated model was inferior

in every way when tested by the works of the great Italian makers.

Hitherto no distinction had been drawn as regards value among the

productions of the several members of the Amati family. Andrea had

been looked upon as equivalent to Girolamo, Antonio, or Niccol�;

but attention now began to be directed towards the works of the

brothers, and to those of Niccol� in particular, as the flat model

gained in the appreciation of the Fiddling world. Grand Amatis became

the coveted Fiddles; they were put up frequently at twice the value

of the smaller patterns—a position they still maintain. The

taste for the flat form having thus been developed, the works of

Antonio Stradivari came to the front, slowly but surely; their beauties

now became known outside the circle in which they had hitherto been

moving: a circle made up chiefly of royal orchestras (where they

were used at wide intervals), convent choirs, and private holders,

who possessed them without being in the least aware of their merits.

They were now eagerly sought by soloists in all parts of Europe,

who spread their fame far and wide. Their exquisite form and finish

captivating the dilettanti, the demand increased to

an extent far beyond that commanded by the works of the Amati at

the height of their popularity. There were a few

Stradivari instruments in England when Amati was the favourite maker,

and their value at that period may be estimated, if it be true that

Cervetto, the father of the famous Violoncellist, was unable to

dispose of a Stradivari Violoncello for five pounds—a circumstance

which shows how blind our forefathers were to the merits of the

greatest maker the world has had. Among the artists of the early

part of the present century who used the instruments of Stradivari

were Boccherini, Viotti, Rode, Kreutzer, Habeneck, Mazas, Lafont,

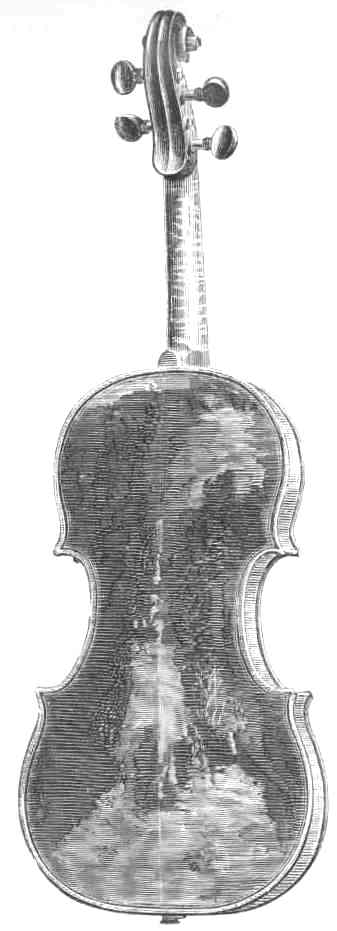

and Baillot. About the year 1820

the fame of Giuseppe Guarneri as a great maker was published beyond

Italy, chiefly through the instrumentality of Paganini. That wonderful

player came to possess a splendid specimen of Guarneri del Ges�,

dated 1743, now sleeping in the Museum at Genoa, which Paganini

used in his tour through France and England. He became the owner

of this world-famed Violin in the following curious manner. A French

merchant (M. Livron) lent him the instrument to play upon at a concert

at Leghorn. When the concert had concluded, Paganini brought it

back to its owner, when M. Livron exclaimed, "Never will I

profane strings which your fingers have touched; that instrument

is yours." A more fitting present or higher compliment could

not have been offered. The names of Amati and Stradivari became

familiar to the musical world gradually, but Guarneri, in the hands

of a Paganini, came forth at a bound. This illustrious Violin was

often credited with the charm which belonged to the performer; the

magical effects and sublime strains that he drew forth from it must,

it was thought, rest in the Violin. Every would-be Violinist, whose

means permitted him to indulge in the luxury, endeavoured to secure

an instrument by the great Guarneri. The demand thus raised brought

forth those gems of the Violin-maker's art, now in the possession

of wealthy amateurs and a few professors. When the various works

of the gifted Guarneri were brought to light, much surprise was

felt that such treasures should have been known to such a handful

of obscure players, chiefly in the churches of Italy. The Violin

used by Paganini belongs to the last period of the great maker,

and consequently, is one of those bold and massive instruments of

his grandest conception, but lacks the beautiful finish of the middle

period. The connoisseurs of those days had associated Giuseppe Guarneri

with Violins of the type of Paganini's only; their surprise was

great when it was discovered that there were three distinct styles

in the works of Guarneri, one evidencing an artistic grandeur, together

with a high finish, but little inferior to those of Antonio Stradivari.

The marked difference between these epochs of Guarneri's manufacture

has led to a great amount of misconception. Fifty years since, the

world possessed little information on the subject, and the connoisseur

of those times could not believe it possible that these varied styles

emanated from one mind. The opportunities given to the connoisseur

of later days of comparing the various instruments of the several

epochs of Guarneri have set at rest all doubts concerning them.

They no longer require dates or labels; they are as easily distinguished

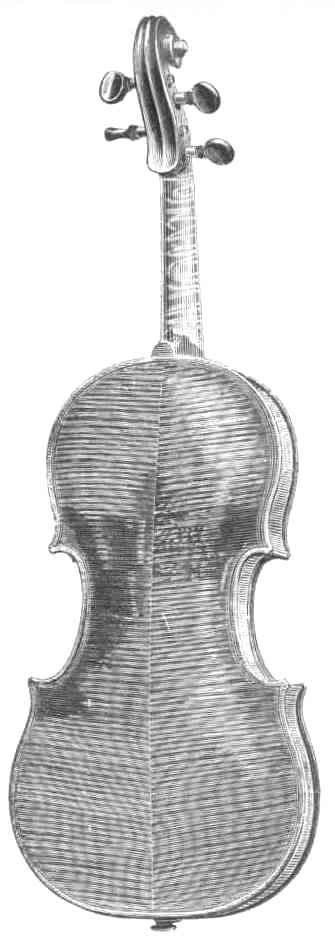

and classed as the works of Amati or Stradivari. Attention was claimed

for the works of Maggini by the charming Belgian Violinist, Charles

de B�riot, who, early admiring the large proportions and powerful

tone of Maggini's instruments, decided to use one for public playing.

That an artist so refined as De B�riot, and one who attached so

much importance to that sympathy between the Violin and player which

should make it the vehicle for presenting its master's inward feelings,

should have selected a Violin of large size, and adapted for giving

forth a great volume of tone, was a matter of surprise to a great

many of his contemporaries. Those who judged only from his school

of playing anticipated that he would have selected Amati as embodying

the qualities he so passionately admired. It is certain, however,

that he succeeded in bringing the penetrating power of his Maggini

thoroughly under his control. In the instruments of Maggini, De

B�riot doubtless recognised the presence of vast power, together

with no inconsiderable amount of purity of tone, and to bring forth

these qualities to the best advantage was with him a labour of love.

The popularity of Maggini's Violins rapidly raised their value.

Instruments that, before De B�riot made them widely known, might

have been purchased for ten pounds, realised one hundred. The Violin

known as "De B�riot's Maggini" remained in his possession

till within a short time of his death, when it was disposed of to

his friend and patron, the Prince de Chimay, it is said, for the

enormous sum of six hundred pounds—a price far in excess of

the average value of Maggini's instruments. In this instance, the

association of De B�riot with the instrument is sufficient, perhaps,

to account for the rare price set upon it. We now reach the

time when Carlo Bergonzi began to be regarded as a maker of the

first class. As a Cremonese maker, he was one of the latest to receive

the attention to which his exceptional merits fairly entitled him.

To English connoisseurs belongs the credit of appreciating this

great maker. The recognised merits

of the makers already named naturally caused a demand for Italian

instruments generally. If the masters could not be had, the pupils

must be found; hence a whole host of Italian makers, quite unknown

in England fifty years since, became familiar to the connoisseur.

The works of Guadagnini, Gagliano, Grancino, Santo Serafino, Montagnana,

and others whose names it is unnecessary to give, passed from Italy

into France and England, until the various schools of Italian Violin

manufacture were completely exhausted. When we look back, it is

surprising that so much has been achieved in such a brief space

of time. The knowledge of Italian works in 1800 was of the slenderest

kind, both in France and England; in less than three-quarters of

a century those countries contrived to possess themselves of the

finest specimens of Cremonese instruments, together with those of

other Italian schools. We here have an example of the energy and

skill that is brought to bear upon particular branches of industry

when once a demand sets in. Men of enterprise rise with it unnoticed,

and lead the way to the desired end. In the case of Italian Violins

it was Luigi Tarisio who acted as pioneer—a being of singular

habits, whose position in the history of the Violin, considered

as a curiosity, is an important one. This remarkable man was born

of humble parents, wholly unconnected with the musical art. In due

time he chose the trade of a carpenter, which vocation he followed

with assiduity, if not with love. He amused himself during his leisure

hours in acquiring a knowledge of playing on the Violin—an

accomplishment that was destined to exercise an influence on his

future life, far greater than was ever contemplated by the young

carpenter. That his playing was not of a high order may be readily

imagined: it was confined chiefly to dance-music, with which he

amused his friends, Fiddling to their dancing. His first Violin

was a very common instrument, but it served to engender within him

that which afterwards became the ruling passion of his life. His

study of this little instrument was the seed from which grew his

vast knowledge of Italian works. So much was his attention absorbed

by the form of the instrument that any skill in playing upon it

became quite a secondary consideration. He endeavoured to see all

the Violins within his reach, and to observe their several points

of difference. The passion for old Violins, thus awakened, caused

him to relinquish his former employment entirely, and to devote

the whole of his attention to the art which he so loved. He soon

became aware of the growing demand for Italian works, and felt that,

possessed with a varied and proficient knowledge of the different

styles of workmanship belonging to the Italian schools of Violin-making,

he could turn his present acquirements to a profitable as well as

pleasurable use. He resolved to journey in search of hidden Cremonas.

His means were, indeed, very limited. His stock-in-trade consisted

only of a few old Violins of no particular value. With these he

commenced his labours, journeying in the garb of a pedlar, on foot,

through Italian cities and villages, and often playing his Violin

in order to procure the bare means of existence. Upon entering a

village he endeavoured to ingratiate himself with the villagers,

and thus obtain information of the whereabouts of any inhabitants

who were possessed of any member of the Fiddle family, his object

being to examine and secure, if possible, such instruments as were

possessed of any merit. It can readily be conceived that at the

commencement of the present century, numbers of valuable Cremonese

and other instruments were in the hands of very humble people. Luigi

Tarisio knew that such must be the case, and made the most of his

good fortune in being the first connoisseur to visit them. His usual

method of trading was to exchange with the simple-minded villagers,

giving them a Violin in perfect playing order for their shabby old

instrument that lacked all the accessories. It was indeed the case

of Aladdin's Lamp, and as potent were these Fiddles as the wonderful

lamp or ring itself. In the possession of Luigi Tarisio they drew

forth from the purses of the wealthy gold that would have enabled

the humble villagers to have ceased labour. It is an axiom, however,

that everything on this earth is only of value providing it is in

its proper place, and these rare old instruments, in the keeping

of the poor peasants, could scarcely be considered to be in their

proper element; their ignorant possessors were alike unable to appreciate

their sterling worth, as works of art, or their powers of sound.

Luigi Tarisio, after gathering together a number of old rarities,

made for his home, and busied himself in examining the qualities

of his stock, selecting the best works, which he laid aside. With

the residuum of those instruments he would again set out, using

them as his capital wherewith to form the basis of future transactions

among the peasantry and others. He visited the numerous monasteries

throughout Italy that he might see the valuable specimens belonging

to the chapel orchestras. He found them often in a condition ill

becoming their value, and tendered his services to regulate and

put them into decent order—services gladly accepted and faithfully

performed by the ardent connoisseur. By the handling of these buried

treasures, his knowledge and experience were greatly extended. Makers

hitherto unknown to him became familiar. When he met with instruments

apparently beyond the repairer's skill, he would make tempting offers

of purchase, which were often accepted. Having accumulated many

instruments of a high order during these journeys, he began to consider

the best means of disposing of them. He decided upon visiting Paris.

He took with him the Violins he valued least, resolving to make

himself acquainted with the Parisian Fiddle market before bringing

forth his treasures. It is said that he undertook his journey on

foot, depriving himself often of the common necessaries of life,

that he might have more money to buy up his country's Fiddles. His

first visit to Paris was in 1827, an eventful year in the history

of Italian Violins, as far as relates to Paris. Upon arriving in

the French capital, he directed his steps to the nearest luthier,

one Aldric, to whom he had been recommended as a purchaser of old

instruments of high value. Upon arriving at the shop of M. Aldric,

Tarisio hesitated before entering, feeling suddenly that his appearance

was scarcely in keeping with his wares, his clothes being of the

shabbiest description, his boots nearly soleless, and his complexion,

naturally inclined to blackness, further darkened by the need of

ordinary ablutions. However, he set aside these thoughts, and introduced

himself to the luthier as having some Cremona Violins for sale.

Aldric regarded him half-contemptuously, and with a silent intent

to convey to Tarisio that he heard what he said, but did not believe

it. The Italian, to the astonishment of the luthier, was not long

in verifying his statement; he opened his bag and brought forth

a beautiful Niccol� Amati, of the small pattern, in fine preservation,

but having neither finger-board, strings, nor fittings of any kind.

The countenance of the luthier brightened when he beheld this unexpected

specimen of the Italian's wares. He carefully examined it, and did

his best to disguise the pleasurable feelings he experienced. He

demanded the price. The value set on it was far in excess of that

he had anticipated; he erroneously arrived at the probable cost

from an estimate of the shabby appearance of the man. He had been

comforting himself that the Italian was unaware of the value put

upon such instruments. He decided to see further the contents of

the bag before expressing an opinion as to the price demanded for

the Amati. Violins by Maggini, Ruggeri, and others, were produced—six

in number. Tarisio was asked to name his price for the six. After

much giving and taking they became the property of the luthier.

This business was not regarded as satisfactory by Tarisio; he had

overestimated the value of his goods in the Paris market; he had

not learned that it was he himself who was to create the demand

for high-class Italian instruments by spreading them far and wide,

so that their incomparable qualities might be observed. He returned

to Italy with his ardour somewhat cooled; the ready sale at the

prices he had put upon his stock was not likely to be realised,

he began to think. However, with the proceeds of his Paris transaction

he again started in search of more Cremonas, with about the same

satisfactory results. He resolved to visit Paris again, taking with

him some of his choicest specimens. He reached the French capital

with a splendid collection—one that in these days would create

a complete furorethroughout the world of Fiddles. He

extended his acquaintance with the Parisian luthiers, among whom

were MM. Vuillaume, Thibout, and Chanot senior. They were all delighted

with the gems that Tarisio had brought, and encouraged him to bring

to France as many more as he could procure, and at regular intervals.

He did so, and obtained at each visit better prices.

This remarkable man

may be said to have lived for nought else but his Fiddles. Mr. Charles

Reade, who knew him well, says:1"The man's whole

soul was in Fiddles. He was a great dealer, but a greater amateur;

he had gems by him no money would buy from him.It is related

of him that he was in Paris upon one occasion, walking

along the Boulevards with a friend, when a handsome equipage belonging

to a French magnate passed, the beauty of which was the talk of

the city. Tarisio's attention being directed to it by his friend,

he calmly answered him that "he would sooner possess one

'Stradivari' than twenty such equipages." There is a very

characteristic anecdote of Tarisio, which is also related by Mr.

Reade in his article on Cremona Violins, entitled the "Romance

of Fiddle-dealing": "Well, one day

Georges Chanot, senior, made an excursion to Spain, to see if he

could find anything there. He found mighty little, but coming to

the shop of a Fiddle-maker, one Ortega, he saw the belly of an old

Bass hung up with other things. Chanot rubbed his eyes, and asked

himself was he dreaming? the belly of a Stradivari Bass roasting

in a shop window! He went in, and very soon bought it for about

forty francs. He then ascertained that the Bass belonged to a lady

of rank. The belly was full of cracks; so, not to make two bites

of a cherry, Ortega had made a nice new one. Chanot carried this

precious fragment home and hung it up in his shop, but not in the

window, for he was too good a judge not to know that the sun will

take all the colour out of that maker's varnish. Tarisio came in

from Italy, and his eye lighted instantly on the Stradivari belly.

He pestered Chanot till the latter sold it him for a thousand francs,

and told him where the rest was. Tarisio no sooner knew this than

he flew to Madrid. He learned from Ortega where the lady lived,

and called on her to see it. 'Sir,' says the lady, 'it is at your

disposition.' That does not mean much in Spain. When he offered

to buy it, she coquetted with him, said it had been long in her

family; money could not replace a thing of that kind, and, in short,

she put on the screw, as she thought, and sold it him

for about four thousand francs. What he did with the Ortega belly

is not known; perhaps sold it to some person in the toothpick trade.

He sailed exultant for Paris with the Spanish Bass in a case. He

never let it go out of his sight. The pair were caught by a storm

in the Bay of Biscay; the ship rolled; Tarisio clasped his Bass

tightly and trembled. It was a terrible gale, and for one whole

day they were in real danger. Tarisio spoke of it to me with a shudder.

I will give you his real words, for they struck me at the time,

and I have often thought of them since. 'Ah, my poor Mr. Reade,

the Bass of Spain was all but lost!' "Was not this

a true connoisseur—a genuine enthusiast? Observe, there was

also an ephemeral insect called Luigi Tarisio, who would have gone

down with the Bass; but that made no impression on his mind. De

minimis non curat Ludovicus! "He got it safe

to Paris. A certain high-priest in these mysteries, called Vuillaume,

with the help of a sacred vessel, called the glue-pot, soon re-wedded

the back and sides to the belly, and the Bass now is just what it

was when the ruffian Ortega put his finger in the pie. It was sold

for 20,000 fr. (�800). I saw the Spanish Bass in Paris twenty-five

years ago, and you can see it any day this month you like, for it

is the identical Violoncello now on show at Kensington numbered

188. Who would divine its separate adventures, to see it all reposing

so calm and uniform in that case?—Post tot naufragia tutus." 1 "Cremona Violins," Pall

Mall Gazette, August, 1872. The love of Tarisio

for the masterpieces of the great makers was so intense, that often

when he had parted with the works he so admired, he never lost sight

of them, and waited a favourable opportunity for again making himself

their owner. It is related of

him that upon one occasion he disposed of a beautiful Stradivari,

in perfect preservation, to a Paris dealer. After having done so

he hungered for it again. For years he never visited Paris without

inquiring after his old favourite, and the possibility of its again

being offered for sale, that he might regain possession of it. At

last his perseverance was rewarded, inasmuch as he heard that it

was to be bought. He instructed his informant to obtain for him

a sight of it. The instrument was fetched, and Tarisio had scarcely

patience enough to wait the opening of the case, so anxious was

he to see his old companion. He eagerly took up the Violin, and

turned it over and over, apparently lost to all about him, when

suddenly his keen eye rested upon a damage it had received, which

was hidden by new varnish. His heart sank within him; he was overcome

by this piece of vandalism. In mingled words of passion and remorse

he gave vent to his feelings. He placed it in its case, remarking

sadly that it had no longer any charm for him. In the year 1851

Tarisio visited England, when Mr. John Hart, being anxious that

he should see the chief collections of Cremonese instruments in

this country, accompanied him to the collection, amongst others,

of the late Mr. James Goding, which was then the finest in Europe.

The instruments were arranged on shelves at the end of a long room,

and far removed from them sat the genuine enthusiast, patiently

awaiting the promised exhibition. Upon Mr. Goding taking out his

treasures he was inexpressibly astonished to hear his visitor calling

out the maker of each instrument before he had had time to advance

two paces towards him, at the same time giving his host to understand

that he thoroughly knew the instruments, the greater number having

been in his possession. Mr. Goding whispered to a friend standing

by, "Why, the man must certainly smell them, he has not had

time to look." Many instruments in this collection Tarisio

seemed never tired of admiring. He took them up again and again,

completely lost to all around—in a word, spell-bound. There

was the "King" Guarneri—the Guarneri known as Lafont's—the

beautiful Bergonzi Violin—the Viola known as Lord Macdonald's—General

Kidd's Stradivari Violoncello—the Marquis de la Rosa's Amati—Ole

Bull's Guarneri—the Santo Serafino 'Cello—and other

remarkable instruments too numerous to mention. Who can say what

old associations these Cremona gems brought to his memory? For the

moment, these Fiddles resolved themselves into a diorama, in which

he saw the chief events of his life played over again. With far

greater truthfulness than that which his unaided memory could have

supplied, each Fiddle had its tale to relate. His thoughts were

carried back to the successful energies of his past. Tarisio may be said

to have lived the life of a hermit to the time of his death. He

had no pleasures apart from his Fiddles; they were his all in this

world. Into his lodgings, in the Via Legnano, near the Porta Tenaglia,

in Milan, no living being but himself was ever permitted to enter.

His nearest neighbours had not the least knowledge

of his occupation. He mounted to his attic without exchanging a

word with any one, and left it securely fastened to start on his

journeys in the same taciturn manner. He was consequently regarded

as a mysterious individual, whose doings were unfathomable. The

time, however, has arrived when the veil hiding the inner life of

this remarkable man should be lifted, and here I am indebted for

particulars to Signor Sacchi, of Cremona, who received them from

a reliable source. Tarisio had been seen by his ever-watchful neighbours

to enter his abode, but none had noticed him quit it for several

days. The door was tried and found locked; no answer was returned

to the sundry knockings. That Tarisio was there the neighbours were

convinced. The facts were at once brought under the notice of the

municipal authorities, who gave instructions that an entry should

be made by force into the mysterious man's apartment. The scene

witnessed was indeed a painful one. On a miserable couch rested

the lifeless body of Luigi Tarisio; around, everything was in the

utmost disorder. The furniture of the apartment consisted mainly

of a chair, table, and the couch upon which lay the corpse. A pile

of old Fiddle-boxes here and there, Fiddles hung around the walls,

others dangling from the ceiling, Fiddle-backs, Fiddle-heads, and

bellies in pigeon-holes; three Double-Basses tied to the wall, covered

with sacking. This was the sight that met the gaze of the authorities.

Little did they imagine they were surrounded with gems no money

would have bought from their late eccentric owner. Here were some

half-dozen Stradivari Violins, Tenors, and Violoncellos, the chamber

Gasparo da Sal� Double-Bass now in the possession of Mr. Bennett,

and the Ruggeri now belonging to Mr. J. R. Bridson, besides upwards

of one hundred Italian instruments of various makers, and others

of different nationalities. All these were passed over by the visitors

as so much rubbish in their search for something more marketable.

At last they alighted on a packet of valuable securities together

with a considerable amount of gold. A seal was placed upon the apartment,

pending inquiries as to the whereabouts of the dead man's relatives.

In due time, some nephews came forth and laid claim to the goods

and chattels of the Italian Fiddle connoisseur. Luigi Tarisio died

in October, 1854. Three months later, upon the news being communicated

to M. Vuillaume, of Paris, he soon set out for Milan, and had the

good fortune to secure the whole of the collection, at a price which

left him a handsome profit upon the transaction, besides the pleasurable

feeling of becoming the possessor of such a varied and remarkable

number of instruments. Having given the

reader all the information I have been able to collect concerning

Tarisio, I will only add that he had advantages over all other connoisseurs,

inasmuch as he found the instruments mostly in their primitive condition,

and free from any tampering as regards the labels within them. He

was thus enabled to learn the characteristics of each without fear

of confusion. The days of taking out the labels of unmarketable

names and substituting marketable counterfeits had not arrived. The principal buyers

of Italian instruments on the Continent, when dealing in this class

of property was in its infancy, were Aldric, MM. Chanot senior,

Thibout, Gand, Vuillaume of Paris, and Vuillaume of Brussels. In

London, among others, were Davis, Betts, Corsby, and John Hart.

There is yet another, the omission of whose name would be a blemish

in any notice of the Violin and its connoisseurs. I refer to Mr.

Charles Reade, the novelist, who in early life took the highest

interest in old Italian Violins. We are indebted to him in a great

measure for bringing into this country many of the most beautiful

specimens we possess. Impressed with the charms of the subject,

he visited the Continent for the pleasure it afforded him of bringing

together choice specimens, and thus opened up the intercourse between

England and the Continent for the interchange of old Violins which

continues to this day. It would be difficult to find an instance

where the intricacies of the subject were so quickly mastered as

in his case. Without assistance, but solely from his own observation,

he gained a knowledge which enabled him to place himself beside

the Chief Continental connoisseurs, and compete for the ownership

of Cremonese masterpieces. These were the men who laid bare the

treasures of Cremona's workshops, and spread far and wide love and

admiration for the fine old works. Connoisseurship such as theirs

is rare. To a keen eye was united intense love of the art, patience,

energy, and memory of no ordinary kind, all of them attributes requisite

to make a successful judge of Violins. Charles Lamb, on

being asked how he distinguished his "ragged veterans"

in their tattered and unlettered bindings, answered, "How does

a shepherd know his sheep?" It has been observed that, "Touch

becomes infinitely more exquisite in men whose employment requires

them to examine the polish of bodies than it is in others. In music

only the simplest and plainest compositions are relished at first;

use and practice extend our pleasure—teach us to relish finer

melody, and by degrees enable us to enter into the intricate and

compounded pleasure of harmony." Thus it is with connoisseurship

in Violins. Custom and observation, springing from a natural disposition,

make prominent features and minute points of difference before unseen,

resulting in a knowledge of style of which it has been well said

"Every man has his own, like his own nose." As an ardent votary

of the Violin, regarded from a point of view at once artistic and

curious, Count Cozio di Salabue takes precedence of all others.

He was born about the time when the art of Italian Violin-making

began to show signs of decadence, and having cultivated a taste

for Cremonese instruments, he resolved to gratify his passion by

bringing together a collection of Violins which should be representative

of the work and character of each maker, and serve as models to

those seeking to tread the path of the makers who made Cremona eminent

as a seat of Violin manufacture. Virtuosity emanating from a spirit

of beneficence is somewhat rare. When, however, utility occupies

a prominent place in the thoughts of the virtuoso, he becomes a

benefactor. The virtuosity of Count Cozio was of this character.

His love for Cremonese instruments was neither whimsical nor transient.

From the time when he secured the contents of the shop of Stradivari

to the end of his life—a period of about fifty years—he

appears to have exerted himself to obtain as much information as

possible relative to the art, and to collect masterpieces that they

might in some measure be the means of recovering a lost art. When

in the year 1775 he secured ten instruments out of ninety-one which

Stradivari left in his shop at the time of his death, he must surely

have considered himself singularly fortunate, and the happiest of

collectors. That such good fortune prompted him to make fresh overtures

of purchase cannot be wondered at. We learn from the correspondence

of Paolo Stradivari that the Count had caused two letters to be

sent by the firm of Anselmi di Briata to Paolo inquiring if he was

willing to part with the tools and patterns used by his father Antonio,

and that Paolo replied on May 4, 1776: "I have already told

you that I have no objection to sell all those patterns, measures,

and tools which I happen to have in my possession, provided that

they do not remain in Cremona, and you will recollect that I have

shown you all the tools I have, and also the box containing the

patterns.... I place all at your disposal, and as it is simply a

friendly matter" (Paolo Stradivari appears to have had large

dealings in cloth and other goods with the firm of Anselmi di Briata,

of Casale, a small city on the Po), "I will give you everything

for twenty-eight giliati."It does not appear that Paolo's correspondents

were moved in their answer by any feelings of sentimentality or

of friendship: on the contrary, the tone of the letter was clearly

commercial, they having made an offer of twenty-three giliati less

than demanded. Paolo Stradivari in his reply, dated June 4, 1776,

says: "Putting ceremony aside, I write in a mercantile style.

I see from your favour of the 13th ultimo (which I only received

by the last courier), that you offer me five giliati for all the

patterns and moulds which I happen to possess, as well as for those

lent to Bergonzi, and also for the tools of the trade of my late

father; but this is too little; however, to show you the desire

I have to please you, and in order that not a single thing belonging

to my father be left in Cremona, I will part with them for six giliati,

providing that you pay them at once into the hands of Domenico Dupuy

& Sons, silk stocking manufacturers. I will send you the things

above-mentioned, conditionally that I keep the five giliati and

use the other one to defray expenses for the case, the packing,

and the custom-house duty, which will be necessary to send them,

and I shall let you have back through Messrs. Dupuy, residing under

the Market Arcades in Turin, any balance that should remain, or

(if you like) you may pay the said Messrs. Dupuy seven giliati,

and I shall then defray all the expenses, and send also the two

snake-wood bows which I possess.—(Signed) PAOLO STRADIVARI." In reply to this

interesting letter, Messrs. Anselmi di Briata appear to have written

accepting the terms offered by Paolo Stradivari, and to have explained

to him that they had been in treaty with a certain Signor Boroni,

relative to the purchase of a Violin, and having come to terms they

wished the instrument to be packed with the tools and moulds. Paolo,

in acknowledging this communication, June 25, 1776, says: "In

reply to your favour of the 10th instant, Signor Boroni will hand

me over the Violin upon hearing that the money has been paid to

Messrs. Dupuy. I shall then have no objection to place it in the

same case together with the patterns and implements left by my father."

From this and subsequent correspondence we learn that Messrs. Anselmi

di Briata, being wholesale traders, were in a suitable position

to act as intermediaries in the purchase of Violins on behalf of

Count Cozio. Their business necessitated their visiting Cremona,

and thus they appear to have seen the Violin of Signor Boroni, and

also another belonging to a monk or friar named Father Ravizza,

both of which were subsequently bought, as seen by the following

extracts from a letter of Paolo Stradivari:— "Cremona, July

10, 1776. We learn from Messrs. Dupuy of the receipt of the seven

giliati, which you have paid on our account.... As we have already

prepared everything, we shall therefore inform Father Ravizza and

Signor Boroni; I have, however, to mention that I did not think

I possessed so many things as I have found. It being according to

what has been promised, it cannot be discussed over again.... It

will be a very heavy case, on account of the quantity of patterns

and tools, and consequently it will be dangerous to put the Violins

in the same package." The writer refers to the two instruments

before mentioned: "I fear without care they will let it fall

in unloading it, and the Violins will be damaged; I inform you therefore

of the fact.... You must let me know how I have to send the case.

If by land, through the firm of Tabarini, of Piacenza, or to take

the opportunity of sending by the P�." In passing, it may be

remarked that the distance between Cremona and Casale by the river

P� is about sixty miles. The later correspondence makes known the

fact of the precious freight having been consigned to the firm of

Anselmi di Briata by way of the P�, and that it was entrusted to

the care and charge of a barge-master named Gobbi. It is by no means

uncommon to discover the memories of men kept green in our minds

from causes strangely curious and unexpected. Many seek to render

their names immortal by some act the nature of which would seem

to be imperishable, and chiefly fail of their object; whilst others,

obscure and unthought of, live on by accident. Imagine the paints

and brushes, the pencils and palettes, the easel and the sketches

of Raffaele having been given over to a P� barge-master, and that

chance had divulged his name. Would he not in these days of microscopic

biography have furnished work for the genealogist, and been made

the subject of numberless pictures? Hence it is that the admirers

of Stradivari cannot fail to remember the name of honest Gobbi,

who carried the chest wherein were the tools with which the Raffaele

of Violin-making wrought the instruments which have served to render

his memory immortal. Soon after the date

of Paolo's last letter, he became seriously ill, dying on the 9th

of October, 1776. The correspondence was then taken up by his son

Antonio. He says in his letter dated November 21, 1776: "I

shall send you the case with the patterns and tools of my late grandfather

Antonio, which was packed and closed before my father was bedridden.

You will find it well-arranged, with mark on it, and with red tape

and seal as on the Violins already sent to you." He next refers

to other patterns which he found locked up in a chest and which

he believes were unknown or forgotten by his father, and offers

to dispose of them, with a Viola, and concludes by promising to

send the receipts, the copies of which show that the remnants of

the tools and patterns were bought for three giliati. It is unnecessary

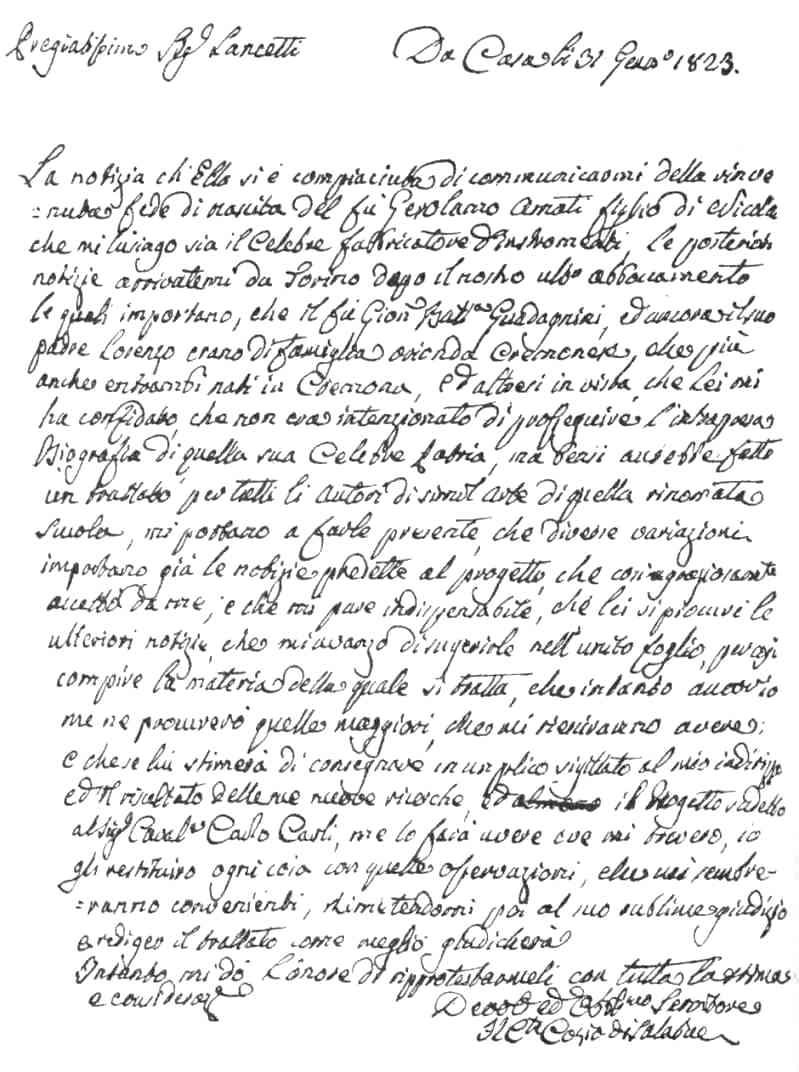

in this place to make further reference to Count Cozio as a collector,

the chief information concerning him being spread over the section

of Italian makers. The facsimile of one of the Count's letters here

given will serve both as an interesting remembrance of him and as

evidence of his keen interest in all relating to the art of which

he was so distinguished a votary.

Probably the earliest

collector of Italian Violins in England was William Corbett. He

was a member of the King's orchestra, and having obtained permission

to go abroad, went to Italy in 1710, and resided at Rome many years,

where he is said to have made a rare collection of music and musical

instruments. How he managed to gratify his desire in this direction

seems not to have been understood by his friends, his means, in

their estimation, not being equal to such an expenditure. Hence

arose a report that he was employed by the Government to watch the

Pretender. Corbett died at an advanced age in 1748, and bequeathed

his "Gallery of Cremonys and Stainers" to the authorities

of Gresham College, with a view that they should remain for inspection

under certain conditions, leaving ten pounds per annum to an attendant

to show the instruments. Whether the wishes of the testator were

carried out in any way there is no information, but the instruments

are said to have been disposed of by auction a short time after

his decease. The principal early

collectors in this country were the Duke of Hamilton, the Duke of

Cambridge, the Earl of Falmouth, the Duke of Marlborough, Lord Macdonald,

and a few others. Later, Mr. Andrew Fountaine, of Narford Hall,

Norfolk, became the owner of several fine Italian instruments, and

made himself better acquainted with the subject, perhaps, than any

amateur of his time. Among the Stradivari Violins which Mr. Fountaine

possessed was that which he purchased from M. Habeneck, the famous

professor at the Paris Conservatoire in the early part of the nineteenth

century. Another very fine specimen of the late period, 1734, was

also owned by him, a Violin of grand proportions in a high state

of preservation, and of the richest varnish. The Guarneri Violins

that he possessed were of a very high class. Among these may be

mentioned a very small Violin by Giuseppe Guarneri, probably unique,

which instrument was exhibited among the Cremonese Violins at the

South Kensington Museum in 1872, together with another of the same

size by Stradivari, and a third by the brothers Amati. The number of rarities

brought together by the late Mr. James Goding was in every respect

remarkable. At one period he owned twelve Stradivari Violins, and

nearly the same number by Giuseppe Guarneri, all high-class instruments.

It would take up too much time and space to name the particular

instruments which were comprised in this collection. The remnant

of this group of Cremonese Fiddles was dispersed by Messrs. Christie

and Manson in 1857. Mr. Plowden's collection was another remarkable

one, consisting of eight instruments of the highest class. The late Joseph Gillott

was a collector, who, in point of number, exceeded all others. He

did not confine himself solely to the works of the greatest makers,

but added specimens of every age and clime; and at one time he must

have had upwards of 500 instruments, the chief part of which belonged

to the Italian School. When it is remembered that the vast multitude

of stringed instruments disposed of by Messrs. Christie and Manson

in 1872 did not amount to one-half the number originally owned by

Mr. Gillott, some idea of the extent of his collection may be gained.

Among the many curious instances of the love of collecting Violins,

which sometimes possesses those unable to use them, perhaps that

of Mr. Gillott is the most singular. Notable collections,

be they of Fiddles, medals, pottery, or pictures, have sometimes

had their rise in accidents of a curious kind. Lord Northwick dated

his passion for coins to a bag of brass ones, which he purchased

in sport for eight pounds. His lordship ended by purchasing, in

conjunction with Payne Knight, the collection of Sir Robert Ainslie,

for eight thousand pounds, besides sharing with the same collector

the famous Sicilian coins belonging to the Prince Torremuzza. The

Gillott collection of Fiddles had its origin in a picture deal.

Mr. Gillott happened to be making terms in his gallery at Edgbaston

relative to an exchange of pictures with Edwin Atherstone, poet

and novelist, who collected both Violins and pictures. A difficulty

arose in adjusting the balance, when Mr. Atherstone suggested throwing

a Fiddle in as a counterpoise. "That would be to no purpose,"

remarked Mr. Gillott, "for I have neither knowledge of music

nor of the Fiddle." "I am aware of that," rejoined

his friend; "but Violins are often of extraordinary value as

works of art." Mr. Gillott, becoming interested in the subject,

agreed to accept the Fiddle as a make-weight, and the business was

settled. A few months later the floor of his picture gallery on

all sides was lined with cases, single and double, containing Violins

in seemingly endless profusion. It was about the year 1848 he conceived

the notion of bringing together this mammoth collection; and in

about four years he had made himself master of the largest number

of Italian instruments ever owned by a single individual. He suddenly

relinquished the pursuit he had followed with such persistency;

he disposed of a great number, and laid the remainder aside in his

steel-pen works at Birmingham, where they slumbered for upwards

of twenty years. The time at last arrived when this pile of Fiddles

was to be dispersed. It fell to my lot to classify them, and never

shall I forget the scene I witnessed. Here, amid the din of countless

machines busy shaping magnum-bonums, swan-bills, and divers other

writing implements, I was about to feast my eyes on some of the

choicest works of the old Italian Fiddle-makers. Passing through

offices, warehouses, and workshops, I found myself at a door which

my conductor set himself to unlock—an act not often performed,

I felt assured, from the sound which accompanied his deed. To adequately

describe what met my eyes when the door swung back on its hinges,

is beyond my powers of description. Fiddles here!—Fiddles

there!—Fiddles everywhere, in wild disorder! I interrogated

my friend as to the cause of their being in such an unseemly condition,

and received answer that he had instructions to remove most of the

instruments from their cases and arrange them, that I might better

judge of their merits. I was at a loss to understand what he meant

by arranging, for a more complete disarrangement could not have

been effected. Not wishing to appear unmindful of the kindly intentions

of my would-be assistant, I thanked him, inwardly wishing that this

disentombment had been left entirely to me. The scene was altogether

so peculiar and unexpected as to be quite bewildering. In the centre

of the room was a large warehouse table, upon which were placed

in pyramids upwards of seventy Violins and Tenors, stringless, bridgeless,

unglued, and enveloped in the fine dust which had crept through

the crevices of the cardboard sarcophagi in which they had rested

for the previous quarter of a century. On the floor lay the bows.

The scene might not inappropriately be compared to a post-mortem

examination on an extended scale. When left alone I began to collect

my thoughts as to the best mode of conducting my inquiry. After

due consideration I attacked pyramid No. 1, from which I saw a head

protruding which augured well for the body, and led me to think

it belonged to the higher walks of Fiddle-life. With considerate

care I withdrew it from the heap, and gently rubbed the dust off

here and there, that I might judge of its breeding. It needed but

little rubbing to make known its character; it was a Viola by Giuseppe

Guarneri, filius Andre�, a charming specimen (now in the ownership

of the Earl of Harrington). Laying it aside, I pulled out from the

pile several others belonging to the same class. Being too eager

to learn of what the real merits of this huge pile of Fiddles consisted,

I rapidly passed from one to the other without close scrutiny, leaving

that for an after pleasure. So entirely fresh were these instruments

to me, that the delight I experienced in thus digging them out may

well be understood by the connoisseur. After thus wading through

those resting on the table, I discovered some shelves, upon which

were a number of cases, which I opened. Here were fine Cremonese

instruments in company with raw copies—as curious a mixture

of good and indifferent as could be well conceived. Not observing

any Violoncellos, when my attendant presented himself I inquired

if there were not some in the collection. I was unable to make him

understand to what I referred for some little time, but when I called

them big Fiddles, he readily understood. He had some faint idea

of having seen something of the kind on the premises, and started

off to make inquiry. Upon his return, I was conducted to an under

warehouse, the contents of which were of a varied character. Here

were stored unused lathes, statuary, antique pianos, parts of machinery,

pictures, and picture-frames. At the end of this long room stood,

in stately form, the "big Fiddles," about fifty in number—five

rows, consequently ten deep. They looked in their cases like a detachment

of infantry awaiting the word of command. Years had passed by since

they had been called upon to take active service of a pacific and

humanising nature in the ranks of the orchestra. Had they the power

of speech, what tales of heroism might they have furnished of the

part they played at the "Fall of Babylon" and the "Siege

of Corinth," aye! and "Wellington's Victory" (Beethoven,

Op. 91). A more curious mixture of art and mechanism could not easily

be found than that which the contents of this room exhibited. With

what delight did I proceed to open these long-closed cases! The

character of the Violins naturally led me to anticipate much artistic

worth in the Violoncellos, and I had not judged erroneously. Bergonzi,

Amati, Andrea Guarneri, Cappa, Grancino, Testore, Landolfi, and

men of less note, were all well represented in this army of big

Fiddles. Having glanced at the merits and demerits of these instruments,

I observed to my conductor that I imagined I had seen all. "No,"

he answered; "I was about to mention that there are a few Violins

at Mr. Gillott's residence, and perhaps we had better go there at

once." I readily assented, and in due time reached Edgbaston.

There seemed no doubt as to the whereabouts of these instruments,

and I was at once ushered into the late Mr. Gillott's bedroom.

Pointing to a long mahogany glazed case occupying one side of the

chamber, the attendant gave me to understand I should there find

the Violins. At once I commenced operations. Pushing aside the first

sliding door, I saw a row of those cardboard cases made to hold

the Violin only, which many of my readers will doubtless remember

seeing at the time of the sale at Messrs. Christie's. By this time

it may readily be imagined that an idea had taken possession of

my mind, that I had not, after all, seen the best portion of the

collection. The circumstance of Violins being deposited in the sleeping

apartment of their owner was sufficient to give birth to this conjecture.

Upon removing the lid of the first cardboard case, my eyes rested

on a charming Stradivari of the Amati period, a gem of its kind.

Gently laying it on the table, that I might examine it later, I

opened the next case. Here rested a magnificent Giuseppe Guarneri,

the instrument afterwards bought by Lord Dunmore, date 1732. Pursuing

my delightful occupation, I opened another case, the contents of

which put the rest completely in the shade—here rested the

Stradivari, date 1715, the gem of the collection. Unable to restrain

my curiosity, I rapidly opened sixteen cases in all, from which

I took out six Stradivari, two Guarneri, one Bergonzi, two Amati,

and five other Violins of a high class. It was observed at

the time of the sale of this remarkable collection, which took place

shortly after the dispersion of Mr. Gillott's gallery of pictures,

that "Every well-ordered display of fireworks should have its

climax of luminous and detonating splendour, throwing into shade

all the preliminary squibs, crackers, and rockets, the Catherine

wheels, the Roman candles, and the golden rain. The French, with

modest propriety, term this consummation a bouquet."

I cannot find anything more applicable than this word to the scene

I have attempted to describe. It only remains for me to say, in

reference to this array of Fiddles, that I passed a week in their

company, and a more enjoyable one I have never had during my professional

career. Dr. Johnson, who

understood neither Fiddling nor painting, who collected neither

coins nor cockle-shells, maggots nor butterflies, was clearly of

the same opinion as the author of "Tristram Shandy," that

there is no disputing against hobby-horses. He says: "The pride

or the pleasure of making collections, if it be restrained by prudence

and morality, produces a pleasing remission after more laborious

studies; furnishes an amusement, not wholly unprofitable, for that

part of life, the greater part of many lives, which would otherwise

be lost in idleness or vice; it produces a useful traffic between

the industry of indigence and the curiosity of wealth, and brings

many things to notice that would be neglected."

Sketch of the Progress of the Violin It may be said that

the Violin made its appearance about the middle of the sixteenth

century. There are instances where reference is made to Violins

and Violin-playing in connection with times prior to that above-named,

but no reliance can be placed on the statements. Leonardo da Vinci,

who died in 1523, is spoken of as having been a celebrated performer

on the Violin. The instrument he used is described as having had

a neck of silver, with the singular addition of a carved horse's

head.1 This description, however, is sufficiently

anomalous to make one rather sceptical, as to whether the instrument

denoted possessed any particular affinity to the present Violin.

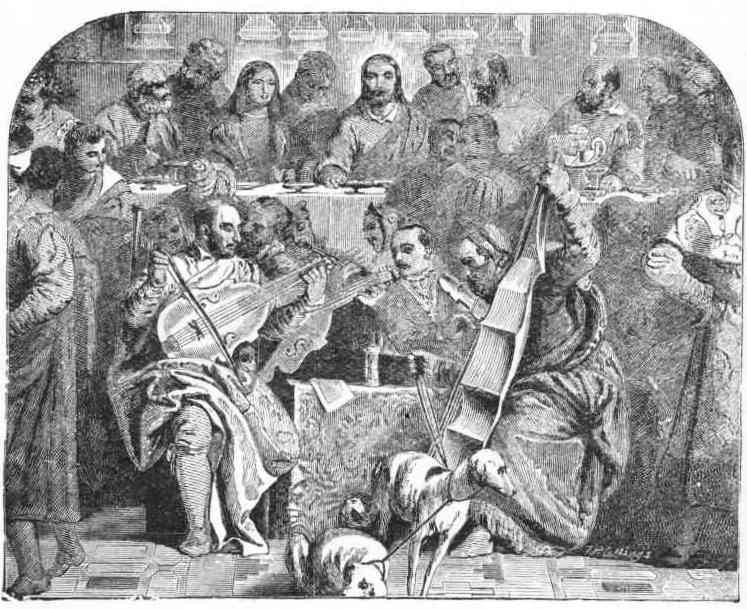

Reference is made to the picture of the "Marriage at Cana,"

by Paolo Veronese, as furnishing evidence of the form of instruments

used in Italy in the 16th century, and a description is given of

the musical part of the subject as follows: "In the foreground,

in the vacant space of the semicircle formed by the table, at which

the guests of the marriage at Cana are seated, Titian is playing

on the Double-Bass, Paolo Veronese and Tintoretto on the Violoncello;

a man with a cross on his breast is playing on the Violin, Bassano

is blowing the Flute, and a Turkish slave the Sackbut."

The naming of the

performers is presumably correct, and greatly heightens our interest

in the group musically. It is clear, however, that the nomenclature

of the instruments is erroneous. In the engraved section of the

famous picture here given, Paolo Veronese is represented taking

part in the performance of a Madrigal, wearing an expression of

countenance indicative of rapt pleasure, engendered by the mingling

of the tones of his Tenor Viol in the harmonies. Behind Paolo Veronese

is seated Tintoretto, playing an instrument identical with that

in the hands of the painter of the picture. On the opposite side

of the table is Titian, with the point of his bow almost touching

the dog, playing the fundamental tones on the Violono. He apparently

displays an amount of real relish for his task, which bespeaks a

knowledge of the responsibility belonging to the post of Basso.

The ecclesiastic seated next to Titian, wearing the chain with crucifix,

is performing on a Soprano Viol. The instruments, in short, are

Italian Viols, the Tenors of which were strung with six strings,

and the Violono, or Bass, with six or seven. It is this order of

Viols to which reference is made in the work of Ganassi del Fontego,

and they are, therefore, distinct from the four-stringed Viols made

at Brescia and Mantua. The earliest player

on the Violin of whom we have any account worthy of attention was

Baltazarini, a native of Piedmont. He removed to France in the year

1577, whither he was sent by Marshal de Brissac to superintend the

music of Catherine de Medici. He was probably the introducer of

Italian dances into Paris, and he delighted the Court as much by

his skill on the Violin as by his writing of ballet music. During the last half

of the sixteenth century a new species of music made way in Italy

which exercised a marked effect on the progress of the Violin, namely,

that of the concert orchestra. It was chiefly cultivated at Venice

and Ferrara. At the latter place the Duke of Ferrara maintained

a great number of musicians in his service. At this period there

were no concerts of a public character; they were given in the palaces

of the wealthy, and the performers were chiefly those belonging

to their private bands. The opera, in which

instruments were used to accompany the voice, began to be put upon

the stage of the public theatres in Italy about the year 1600. The

opera "Orfeo," by Claudio Monteverde, a Cremonese, famous

both as a composer and Violist, was represented in 1608. The opera

in those times differed essentially from that of modern days. Particular

instruments were selected to accompany each character; for instance,

ten Treble Viols to accompany Eurydice, two Bass Viols to Orpheus,

and so on. No mention is made of Violins further than that two small

Violins (duoi Violini piccoli alla Francese) are to accompany the

character of Hope, from which it is inferred that a band of Violins

was in use not much later. It is to the introduction

of the Sonata that the rapid progress in the cultivation of Violin-playing

is due. Dr. Burney tells us the earliest Sonatas or Trios for two

Violins and a Bass he discovered were published by Francesco Turini,

organist of the Duomo, at Brescia, under the following title: "Madrigali

� una, due, e tre voci, con alcune Sonate � due e � tre, Venezia,

1624." He says: "I was instigated by this early date to

score one of these Sonatas, which consisted of only a single movement

in figure and imitation throughout, in which so little use was made

of the power of the bow in varying the expression of the same notes,

that each part might have been as well played on one instrument

as another." In this branch of

composition Corelli shone forth with considerable lustre, and gave

great impetus to the culture of the Violin. It was at Rome that

his first twelve Sonatas were published, in 1683. In 1685 the second

set appeared, entitled "Balletti da Camera"; four years

later the third set was published. The genius of Corelli may be

said to have revolutionised Violin-playing. He had followers in

the chief cities of Italy. There was Vitali at Modena, Visconti

at Cremona (who, it is said, tendered his advice to Stradivari upon

the construction of his instruments—advice, I think, little

needed); Veracini at Bologna, and a host of others. Dibdin, the

Tyrt�us of the British navy, said: "I had always delighted

in Corelli, whose harmonies are an assemblage of melodies. I, therefore,

got his Concertos in single parts, and put them into score, by which

means I saw all the workings of his mind at the time he composed

them; I so managed that I not only comprehended in what manner the

parts had been worked, but how, in every way, they might have been

worked. From this severe but profitable exercise, I drew all the

best properties of harmony, and among the rest I learnt the valuable

secret, that men of strong minds may violate to advantage many of

those rules of composition which are dogmatically imposed."

We must now retrace

our steps somewhat, in order to allude to another Violinist, who

influenced the progress of the leading instrument out of Italy,

viz., Jean Baptiste Lulli. The son of a Tuscan peasant, born in

the year 1633, Lulli's name is so much associated with the romantic

in the history of Violin-playing that he has been deprived in a

great measure of the merits justly his due for the part he took

in the advancement of the instrument. The story of Lulli and the

stew-pans2 bristles with interest for juvenile musicians,

but the hero is often overlooked by graver people, on account of

his culinary associations. When Lulli was admitted to the Violin

band of Louis XIV., he found the members very incompetent; they

could not play at sight, and their style was of the worst description.

The king derived much pleasure from listening to Lulli's music,

and established a new band on purpose for the composer, namely,

"Les petits Violons," to distinguish it from the band

of twenty-four. He composed much music for the Court ballets in

which the king danced. 2: Lulli having shown

a disposition for music, received some instructions on the rudiments

of the art from a priest. The Chevalier de Guise, when on his travels

in Italy, had been requested by Mademoiselle de Montpensier, niece

of Louis XIV., to procure for her an Italian boy as page, and happening

to see Lulli in Florence, he chose him for that purpose, on account

of his wit and vivacity, and his skill in playing on the guitar.

The lady, however, not liking his appearance, sent him into her

kitchen, where he was made an under scullion, and amused himself

by arranging the stew-pans in tones and semitones, upon which he

would play various airs, to the utter dismay of the cook. Lulli contributed

greatly to the improvement of French music. He wrote several operas,

and many compositions for the Church, all of which served to raise

the standard of musical taste in France. To him also belongs the

credit of having founded the French national opera. We will now endeavour

to trace the progress of the Violin in England. It is gratifying

to learn that, even in the primitive age of Violin-playing, we were

not without our national composers for the instrument. Dr. Benjamin

Rogers wrote airs in four parts for Violins so early as 1653 (the

year Corelli was born). John Jenkins wrote twelve sonatas for two

Violins and a Bass, printed in London in 1660, which were the first

sonatas written by an Englishman. About this date Charles II. established

his band of twenty-four Violins. During his residence on the Continent

he had frequent opportunities of hearing the leading instrument,

and seems to have been so much impressed with its beauties that

he set up for himself a similar band to that belonging to the French

Court. The leader was Thomas Baltzar, who was regarded as the best

player of his time. Anthony Wood met Baltzar at Oxford, and says

he "saw him run up his fingers to the end of the finger-board

of the Violin, and run them back insensibly, and all in alacrity

and in very good time, which he nor any one in England saw the like

before." Wood tells us that Baltzar "was buried in the

cloister belonging to St. Peter's Church in Westminster." The

emoluments attached to the Royal band, according to Samuel Pepys,

appear to have been somewhat irregular. In the Diary, December 19,

1666, we read: "Talked of the King's family with Mr. Kingston,

the organist. He says many of the musique are ready to starve, they

being five years behindhand for their wages; nay, Evens, the famous

man upon the Harp, having not his equal in the world, did the other

day die for mere want, and was fain to be buried at the alms of

the parish, and carried to his grave in the dark at night without

one linke, but that Mr. Kingston met it by chance, and did give

12d. to buy two or three links." The state of the

Merry Monarch's exchequer in 1662, according to an extract from

the Emoluments of the Audit Office, seems to have been singularly

prosperous. An order runs as follows: "These are to require

you to pay, or cause to be paid, to John Bannister, one of His Majesty's

musicians in ordinary, the sum of forty pounds for two Cremona Violins,

by him bought and delivered for His Majesty's service, as may appear

by the bill annexed; and also ten pounds for strings for two years

ending 24th June, 1662." The King's band was

led in 1663 by the above-named John Bannister, who was an excellent

Violinist. His name is associated with the earliest concerts in

England, namely, those held at "four of the clock in the afternoon"

at the George Tavern, in Whitefriars. Roger North informs us the

shopkeepers and others went to sing and "enjoy ale and tobacco,"

and the charge was one shilling and "call for what you please." In the year 1683,

Henry Purcell, organist of the Chapel Royal, published twelve sonatas

for two Violins and a Bass. These famous instrumental compositions

were written, the author tells us, in "just imitation of the

most famed Italian masters, principally to bring the seriousness

and gravity of that sort of musick into vogue." Purcell, in

conformity with an age of dedications, thus addressed the Merry

Monarch:— "May it please

your Majesty, I had not assum'd the confidence of laying ye following

compositions at your sacred feet, but that, as they are the immediate

results of your Majestie's Royal favour and benignity to me (which

have made me what I am), so I am constrained to hope I may presume

amongst others of your Majestie's over-obliged and altogether undeserving

subjects that your Majesty will, with your accustomed clemency,

vouchsafe to pardon the best endeavours of your Majestie's "Most humble and obedient

subject and servant,

Charles II. is said

to have understood his notes, and to sing in (in the words of one

who had sung with him) a plump bass, but that he only looked upon

music as an incentive to mirth, not caring for any that he could

not "stamp the time to." The endeavour of his accomplished

and gifted young organist to lead the King and his people to admire