|

THE FRANKS FROM THEIR

FIRST APPEARANCE IN HISTORY TO THE

|

|

PREFACE.

THE conscientious

man, who knows to what straits even the British Museum is put, by the influx of

unnecessary books, will not lightly write, still less publish, a new work. The Author of the

present volume seeks an excuse in the comparative novelty of his subject, and in the ready access he has

enjoyed to the sources of Frankish history, many of which have only been cleared and rendered available

during the last few years by

able editors and commentators in Germany.

The following pages are the result of studies,

the chief object of which was to gain an insight into the age of Charlemagne.

They are offered to the public in the hope that they may throw some little

light on one of the darkest but not least important ages of the world, when, in

the early dawn of modern history, rude hands sowed the seeds of Christian

civilization.

The Author is well aware that he has chosen a subject which has not been

found generally interesting, which is looked on as the property of the

troubadour or the fabling monk, rather than of genuine history. But he thinks

it a legitimate object of ambition to alter or modify these views. If the glory

of Athens gives a charm to the account of Dorian migrations, and lights up even

the distant flitting shades of Pelasgi and Curetes,

if the gorgeous spectacle of Augustan Rome leads us to watch with interest the

feuds and fortunes of the citizens of a poor and small Italian town, there is

no reason why we should remain indifferent to the primordia of the mighty race

whose annals are the history of modern and Christian Europe, to the origin of

the wonderful political and social world in which it is our lot to live.

Should the present volume meet with any degree

of public favor, the Author hopes to bring forward another, on the life and

times of Charlemagne, to which this work, though complete in itself, might form

a kind of introduction.

For the many defects which will be found in his

book, and of which he is himself fully conscious, the Author begs the

indulgence of his friends, on the ground that he has performed it in the

intervals of a laborious and anxious occupation.

In conclusion, the Author cannot omit thus publicly to express his grateful thanks to Professor Ritschl, and the other librarians of the University of Bonn, for the courtesy and kindness with

which they placed their

valuable library at his disposal.

I.

FROM THE FIRST APPEARANCE OF THE

FRANKS TO THE DEATH OF CLOVIS

(AD. 240-511)

It is

well known that the name of “Frank” is not to be found in the long list of

German tribes preserved to us in the “Germania” of Tacitus. Little or nothing

is heard of them before the reign of Gordian III. In AD 240 Aurelian, then a

tribune of the sixth legion stationed on the Rhine, encountered a body of

marauding Franks near Mayence, and drove them back

into their marshes. The word “Francia” is also found

at a still earlier date, in the old Roman chart called the Charta Peutingeria, and occupies on

the map the right bank of the Rhine from opposite Coblentz to the sea. The

origin of the Franks has been the subject of frequent debate, to which French

patriotism has occasionally lent some asperity. At the time when they first

appear in history, the Romans had neither the taste nor the means for

historical research, and we are therefore obliged to depend in a great measure

upon conjecture and combination. It has been disputed whether the word “Frank”

was the original designation of a tribe, which by a change of habitation

emerged at the period above mentioned into the light of history, or that of a

new league, formed for some common object of aggression or defence,

by nations hitherto familiar to us under other names.

We can in

this place do little more than refer to a controversy, the value and interest

of which has been rendered obsolete by the progress of historical

investigation. The darkness and void of history have as usual been filled with

spectral theories, which vanish at the challenge of criticism and before the

gradually increasing light of knowledge.

We need

hardly say that the origin of the Franks has been traced to fugitive colonists

from Troy; for what nation under Heaven has not sought to connect itself, in

some way or other, with the glorified heroes of the immortal song? Nor is it

surprising that French writers, desirous of transferring from the Germans to

themselves the honors of the Frankish name, should have made of them a tribe of

Gauls, whom some unknown cause had induced to settle in Germany, and who

afterwards sought to recover their ancient country from the Roman conquerors.

At the present day, however, historians of every nation, including the French,

are unanimous in considering the Franks as a powerful confederacy of German

tribes, who in the time of Tacitus inhabited the north-western parts of Germany

bordering on the Rhine. And this theory is so well supported by many scattered

notices, slight in themselves, but powerful when combined, that we can only

wonder that it should ever have been called in question. Nor was this

aggregation of tribes under the new name of Franks a singular instance; the

same took place in the case of the Alemanni and Saxons.

The

actuating causes of these new unions are unknown. They may be sought for either

in external circumstances, such as the pressure of powerful enemies from

without, or in an extension of their own desires and plans, requiring the

command of greater means, and inducing a wider co-operation of those, whose

similarity of language and character rendered it most easy for them to unite.

But perhaps we need look no farther for an efficient cause than the spirit of

amalgamation which naturally arises among tribes of kindred race and language,

when their growing numbers, and an increased facility of moving from place to

place, bring them into more frequent contact. The same phenomenon may be

observed at certain periods in the history of almost every nation, and the

spirit which gives rise to it has generally been found strong enough to

overcome the force of particular interests and petty nationalities.

SICAMBRI AND SALIAN FRANKS.

The

etymology of the name adopted by the new confederacy is also uncertain. The

conjecture which has most probability in its favor is that adopted long ago by

Gibbon, and confirmed in recent times by the authority of Grimm, which connects

it with the German word Frank (free). The derivation preferred by Adelung from frak, with the inserted

nasal, differ of Grimm only in appearance. No small countenance is given to

this derivation by the constant recurrence in after times of the epithet

“truces”, “feroces”, which

the Franks were so fond of applying to themselves, and which they certainly did

everything to deserve. Tacitus speaks of nearly all the tribes, whose various

appellations were afterwards merged in that of Frank, as living in the

neighborhood of the Rhine. Of these the principal were the Sicambri (the chief

people of the old Iscaevonian tribe),

who, as there is reason to believe, were identical with the Salian Franks. The

confederation further comprised the Bructeri,

the Ghamavi, Ansibarii, Tubantes, Marsi,

and Chasuarii, of

whom the five last had formerly belonged to the celebrated Cheruscan league, which,

under the hero Arminius, destroyed three Roman legions in the Teutoburgian Forest. The

strongest evidence of the identity of these tribes with the Franks, is the fact

that, long after their settlement in Gaul, the distinctive names of the

original people were still occasionally used as synonymous with that of the

confederation. The Sicambri are well known in the Roman history for their

active and enterprising spirit, and the determined opposition which they

offered to the greatest generals of Rome. It was on their account that Caesar

bridged the Rhine in the neighborhood of Bonn, and spent eighteen days, as he

informs us with significant minuteness, on the German side of that river.

Drusus made a similar attempt against them with little better success. Tiberius

was the first who obtained any decided advantage over them; and even he, by his

own confession, was obliged to have recourse to treachery. An immense number of

them were then transported by the command of Augustus to the left bank of the

Rhine, “that”, as the Panegyrist expresses it, “they might be compelled to lay

aside not only their arms but their ferocity”. That they were not, however,

even then, so utterly destroyed or expatriated as the flatterers of the Emperor

would have us believe, is evident from the fact that they appear again under the

same name, in less than three centuries afterwards, as the most powerful tribe

in the Frankish confederacy.

The

league thus formed was subject to two strong motives, either of which might

alone have been sufficient to impel a brave and active people into a career of

migration and conquest. The first of these was necessity, the actual want of

the necessaries of life for their increasing population, and the second desire,

excited to the utmost by the spectacle of the wealth and civilization of the

Gallic provinces.

As long

as the Romans held firm possession of Gaul, the Germans could do little to

gratify their longings; they could only obtain a settlement in that country by

the consent of the Emperor and on certain conditions. Examples of such merely

tolerated colonization were the Tribocci,

the Vangiones, and

the Ubii at

Cologne. But when the Roman Empire began to feel the numbness of approaching

dissolution, and, as is usually the case, first in its extremities, the Franks

were amongst the most active and successful assailants of their enfeebled foe:

and if they were attracted towards the West by the abundance they beheld of all

that could relieve their necessities and gratify their lust of spoil, they were

also impelled in the same direction by the Saxons, the rival league, a people

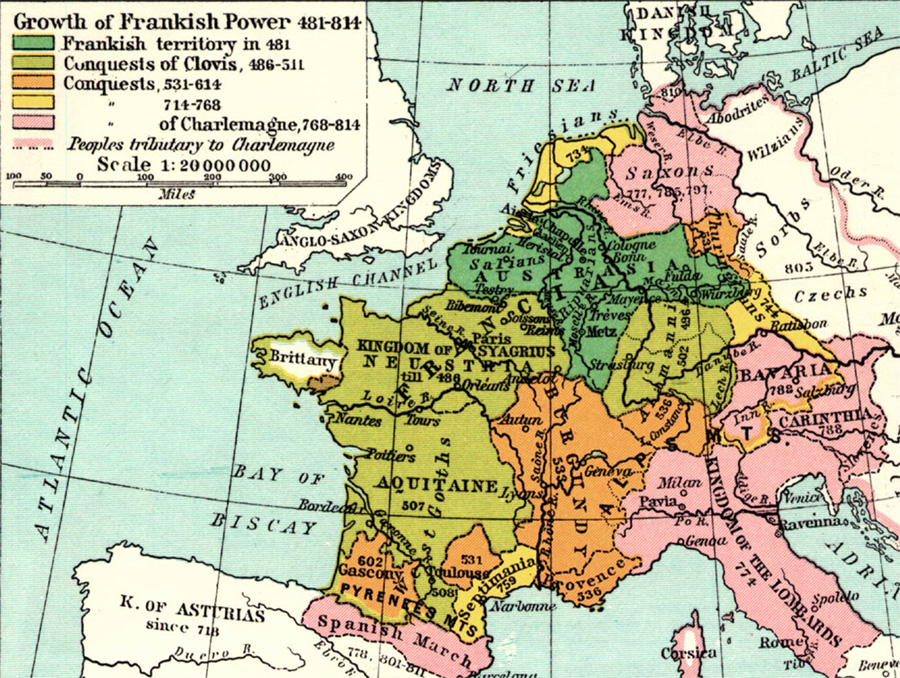

as brave and perhaps more barbarous than themselves. A glance at the map of

Germany of that period will do much to explain to us the migration of the

Franks, and that long and bloody feud between them and the Saxons, which began

with the Gatti and Cherusci and needed all the power and energy of a

Charlemagne to bring to a successful close. The Saxons formed behind the

Franks, and could only reach the provinces of Gaul by sea. It was natural

therefore that they should look with the intensest hatred upon a people who barred

their progress to a more genial climate and excluded them from their share in

the spoils of the Roman world.

PROGRESS OF THE FRANKS IN GAUL.

The

Franks advanced upon Gaul from two different directions, and under the

different names of Salians, and Ripuarians, the former of whom we have reason

to connect more particularly with the Sicambrian tribe. The origin of the words Salian and Ripuarian, which are first used

respectively by Ammianus Marcellinus and Jordanes,

is very obscure, and has served to exercise the ingenuity of ethnographers.

There are, however, no sufficient grounds for a decided opinion. At the same

time it is by no means improbable that the river Yssel, Isala or Sal (for it has borne all these

appellations), may have given its name to that portion of the Franks who lived

along its course. With still greater probability may the name Ripuarii or Riparii,

be derived from Ripa, a term used by the

Romans to signify the Rhine. These dwellers on the Bank were those that

remained in their ancient settlements while their Salian kinsmen were advancing

into the heart of Gaul.

It would

extend the introductory portion of this work beyond its proper limits to refer,

however briefly, to all the successive efforts of the Franks to gain a

permanent footing upon Roman ground. Though often defeated, they perpetually

renewed the contest; and when Roman historians and panegyrists inform us that

the whole nation was several times “utterly destroyed” the numbers and

geographical position in which we find them a short time after every such

annihilation, prove to us the vanity of such accounts. Aurelian, as we have

seen, defeated them at Mayence, in AD 242,

and drove them into the swamps of Holland. They were routed again about twelve

years afterwards by Gallienus; but they quickly recovered from this blow, for

in AD 276

we find them in possession of sixty Gallic cities, of which Probus is said to have deprived them, and to have

destroyed 400,000 of them and their allies on Roman ground. In AD 280,

they gave their aid to the usurper Proculus,

who claimed to be of Frankish blood, but was nevertheless betrayed by them; and

in AD 288,

Carausius the Menapian was

sent to clear the seas of their roving barks. But the latter found it more

agreeable to shut his eyes to their piracies, in return for a share of the

booty, and they afterwards aided in protecting him from the chastisement due to

his treachery, and in investing him with the imperial purple in Britain.

In the

reign of Maximian, we find a Frankish army, probably of Ripuarians, at Treves,

where they were defeated by that emperor; and both he and Diocletian adopted

the title of “Francicus”,

which many succeeding emperors were proud to bear. The first appearance of the

Salian Franks, with whom this history is chiefly concerned, is in the

occupation of the Batavian Islands, in the Lower Rhine. They were attacked in

that territory in ad 292, by Constantius Chlorus, who, as is said, not only drove them out

of Batavia, but marched, triumphant and unopposed, through their own country as

far as the Danube. The latter part of this story has little foundation either

in history or probability.

The more

determined and successful resistance to their progress was made by Constantine

the Great, in the first part of the fourth century. We must, however, receive

the extravagant accounts of the imperial annalists with considerable caution.

It is evident, even from their own language, that the great

emperor effected more by stratagem than by force. He found the Salians once

more in Batavia, and, after defeating them in a great battle, carried off a

large number of captives to Treves, the chief residence of the emperor, and a

rival of Rome itself in the splendor of its public buildings.

It was in

the circus of this city, and in the presence of Constantine, that the notorious

“Ludi Francici” were celebrated; at

which several thousand Franks, including their kings Regaisus and Ascaricus, were compelled to fight with wild

beasts, to the inexpressible delight of the Christian spectators. “Those of the

Frankish prisoners”, says Eumenius, “whose perfidy

unfitted them for military service, and their ferocity for servitude, were

given to the wild beasts as a show, and wearied the raging monsters by their

multitude”. “This magnificent spectacle” Nazarius praises, some twenty years after it had taken place, in the most enthusiastic

terms, comparing Constantine to a youthful Hercules who had strangled two

serpents in the cradle of his empire. Eumenius calls

it a “daily and eternal victory”, and says that Constantine had erected terror

as a bulwark against his barbarian enemies. This terror did not, however,

prevent the Franks from taking up arms to revenge their butchered countrymen,

nor the Alemanni from joining in the insurrection. The skill and fortune of

Constantine generally prevailed; he destroyed great numbers of the Franks and

the “innumeroe gentes” who fought on their

side, and really appears for a time to have checked their progress.

It is

impossible to read the brief yet confused account of these incessant encounters

between the Romans and Barbarians, without coming to the conclusion that only

half the truth is told; that while every advantage gained by the former is

greatly exaggerated, the successes of the latter are passed over in silence.

The most glorious victory of a Roman general procures him only a few months

repose, and the destruction of “hundreds of thousands” of Franks and Alemanni

seems but to increase their numbers. We may fairly say of the Franks, what

Julian and Eutropius have said respecting the Goths, that they were not so

utterly annihilated as the panegyrists pretend, and that many of the victories

gained over them cost “more money than blood”.

The death

of Constantine was the signal for a fresh advance on the part of the Franks.

Libanius, the Greek rhetorician, when extolling the deeds of Constans, the

youngest son of Constantine the Great, says that the emperor stemmed the

impetuous torrent of barbarians “by a love of war even greater than their own”.

He also says that they received overseers; but this was no doubt on Roman

ground, which would account for their submission, as we know that the Franks

were more solicitous about real than nominal possession. During the frequent

struggles for the Purple which took place at this period, the aid of the Franks

was sought for by the different pretenders, and rewarded, in case of success,

by large grants of land within the limits of the empire. The barbarians

consented, in fact, to receive as a gift what had really been won by their own

valor, and could not have been withheld. Even previous to the reign of

Constantine, some Frankish generals had risen to high posts in the service of Roman

emperors. Magnentius, himself a German, endeavored to support his usurpation by

Frankish and Saxon mercenaries; and Silvanus, who was driven into rebellion by

the ingratitude of Constantius, whom he had faithfully served, was a Frank.

The state

of confusion into which the empire was thrown by the turbulence and insolence

of the Roman armies, and the selfish ambition of their leaders, was highly

favorable to the progress of the Franks in Gaul. Their next great and general

movement took place in ad 355, when, along the whole Roman frontier from

Strasburg to the sea, they began to cross the Rhine, and to throw themselves in

vast numbers upon the Gallic provinces, with the full determination of forming

permanent settlements. But again the relenting fates of Rome raised up a hero

in the person of the Emperor Julian, worthy to have lived in the most glorious

period of her history. After one or two unsuccessful efforts, Julian succeeded

in retaking Cologne and other places, which the Germans, true to their

traditionary hatred of walled towns, had laid bare of all defenses.

In the

last general advance of the Franks in ad 355, the Salians had not only once

more recovered Batavia, but had spread into Toxandria,

in which they firmly fixed themselves. It is important to mark the date of this

event, because it was at this time that the Salians made their first permanent

settlement on the left bank of the Rhine, and by the acquisition of Toxandria laid the foundation of the kingdom of Clovis.

Julian indeed attacked them there in ad 358, but he had probably good reasons

for not reducing them to despair, as we find that they were permitted to retain

their newly acquired lands, on condition of acknowledging themselves subjects

of the empire.

He was

better pleased to have them as soldiers than as enemies, and they, having felt

the weight of his arm, were by no means averse to serve in his ranks, and to

enrich themselves by the plunder of the East. Once in undisputed possession of Toxandria, they gradually spread themselves further and

further, until, at the beginning of the fifth century, we find them occupying

the left bank of the Rhine; as may safely be inferred from the fact that Tongres, Arras, and Amiens are

mentioned as the most northern of the Roman stations. At this time they

reached Tournai, which became henceforth the

chief town of the Salian Franks. The Ripuarians, meanwhile, were extending

themselves from Andernach downwards

along the middle Rhine, and gained possession of Cologne about the time of the

conquest of Tournai by their Salian

brethren. On the left of the river they held all that part of Germania Secunda which was not

occupied by the Salians. In Belgica Secunda, they spread themselves

as far as the Moselle, but were not yet in

possession of Treves, as we gather from the frequent assaults made by them upon

that city. The part of Gaul therefore now subject to the Ripuarians was bounded

on the north-west by the Silva Carbonaria,

or Kolhenwald; on the

south-west by the Meuse and the forest of Ardennes; and on the south by

the Moselle.

We shall

be the less surprised that some of the fairest portions of the Roman Empire

should thus fall an almost unresisting prey to barbarian invaders, when we

remember that the defence of the empire itself was

sometimes committed to the hands of Frankish soldiers. Those of the Franks who

were already settled in Gaul, were often engaged in endeavoring to drive back

the ever-increasing multitude of fresh barbarians, who hurried across the Rhine

to share in the bettered fortunes of their kinsmen, or even to plunder them of

their newly-acquired riches. Thus Mallobaudes,

who is called king of the Franks, and held the office of Domesticorum Comes under

Gratian, commanded in the Imperial army which defeated the Alemanni at Argentaria. And, again, in the short reign of Maximus, who

assumed the purple in Gaul, Spain, and Britain, near the end of the fourth

century, we are told that three Frankish kings, Genobaudes, Marcomeres, and Sunno, crossed the Lower Rhine, and plundered the

country along the river as far as Cologne; although the whole of Northern Gaul

was already in possession of their countrymen. The generals Nonnius and Quintinus, whom Maximus had left

behind him at Treves, the seat of the Imperial government in Gaul, hastened to

Cologne, from which the marauding Franks had already retired with their

booty. Quintinus crossed

the Rhine, in pursuit, at Neus,

and, unmindful of the fate of Varus in

the Teutoburgian wood,

followed the retreating enemy into the morasses. The Franks, once more upon

friendly and familiar ground, turned upon their pursuers, and are said to have

destroyed nearly the whole Roman army with poisoned arrows.

The war

continued, and was only brought to a successful conclusion for the Romans by

the courage and conduct of Arbogastes,

a Frank in the service of Theodosius. Unable to make peace with his barbarous

countrymen, and sometimes defeated by them, this general crossed the Rhine when

the woods were leafless, ravaged the country of the Chamavi, Bructeri,

and Catti, and having slain two of their chiefs

named Priam and Genobaudes,

compelled Marcomeres and Sunno to give hostages. The

submission of the Franks must have been of short continuance, for we read that

in ad 398 these same kings, Marcomeres and Sunno, were again found ravaging

the left bank of the Rhine by Stilicho. This famous warrior defeated them

in a great battle, and sent the former, or perhaps both of them, in chains to

Italy, where Marcomeres died

in prison.

The first

few years of the fifth century are occupied in the struggle between Alaric the

Goth and Stilicho, which ended in the sacking of Rome by the former in the year

410 ad, the same in which he died.

While the

Goths were inflicting deadly wounds on the very heart of the empire, the

distant provinces of Germany and Gaul presented a scene of indescribable

confusion. Innumerable hosts of Astingians,

Vandals, Alani, Suevi, and Burgundians, threw

themselves like robbers upon the prostrate body of Imperial Rome, and scrambled

for the gems which fell from her costly diadem. In such a storm the Franks

could no longer sustain the part of champions of the empire, but doubtless had

enough to do to defend themselves and hold their own. We can only guess at the

fortune which befell the nations in that dark period, from the state in which

we find them when the glimmering light of history once more dawns upon the

chaos.

PHARAMOND A MYTHICAL PERSONAGE

Of the

internal state of the Frankish league in these times, we learn from ancient

authorities absolutely nothing on which we can safely depend. The blank is

filled up by popular fable. It is in this period, about 417 ad, that the reign

of Pharamond is placed, of whom we may more than

doubt whether he ever existed at all. To this hero was afterwards

ascribed, not only the permanent conquests made at this juncture by the various

tribes of Franks, but the establishment of the monarchy, and the collection and

publication of the well-known Salic laws.

The sole foundation for this complete and harmonious fabric is a passage

interpolated into an ancient chronicle of the fifth century; and, with this

single exception, Pharamond’s name

is never mentioned before the seventh century. The whole story is perfected and

rounded off by the author of the “Gesta Francorum”,

according to whom, Pharamond was the son of Marcomeres, the prince who

ended his days in the Italian prison. The fact that nothing is known

of him by Gregory of Tours or Fredegarius is

sufficient to prevent our regarding him as an historical personage. To this may

be added that he is not mentioned in the prologue of the Salic law, with which his name has been so intimately

associated by later writers.

Though

well authenticated names of persons and places fail us at this time, it is not

difficult to conjecture what must have been the main facts of the case. Great

changes took place among the Franks, in the first half of the fifth century,

which did much to prepare them for their subsequent career. The greater portion

of them had been mere marauders, like their German brethren of other nations:

they now began to assume the character of settlers; and as the idea of founding

an extensive empire was still far from their thoughts, they occupied in

preference the lands which lay nearest to their ancient homes. There are many

incidental reasons which make this change in their mode of life a natural and

inevitable one. The country whose surface had once afforded a rich and easily

collected booty, and well repaid the hasty foray of weeks, and even days, had

been stripped of its movable wealth by repeated incursions of barbarians still

fiercer than themselves. All that was above the surface the Alan and the Vandal

had swept away, the treasures which remained had to be sought for with the

plough. The Franks were compelled to turn their attention to that agriculture

which their indolent and warlike fathers had hated; which required fixed

settlements, and all the laws of property and person indissolubly connected therewith.

Again, though there is no sufficient reason to connect the Salic laws with the mythical name of Pharamond, or to suppose that they were altogether the work

of this age (since we know from Tacitus that the Germans had similar laws in

their ancient forests), yet it is very probable was insufficiently defended, he

advanced upon that city, and succeeded in taking it. After spending a few days

within the walls of his new acquisition, he marched as far as the river Somme.

His progress was checked by Aetius and Majorian, who surprised him in the

neighborhood of Arras, at a place called Helena (Lens), while celebrating a

marriage, and forced him to retire. Yet at the end of the war, the Franks

remained in full possession of the country which Clodion had overrun; and the

Somme became the boundary of the Salian land upon the south-west, as it

continued to be until the time of Clovis.

Clodion

died in AD 448, and was thus saved from the equally

pernicious alliance or enmity of the ruthless conqueror Attila. This “Scourge

of God”, as he delighted to be called, appeared in Gaul about the year 450 AD,

at the head of an innumerable host of mounted Huns; a race so singular in their

aspect and habits as to seem scarcely human, and compared with whom, the

wildest Franks and Goths must have appeared rational and civilized beings.

FRANKS AT CHÂLONS.

The time

of Attila’s descent upon the Rhine was well chosen for the prosecution of his

scheme of universal dominion. Between the fragment of the Roman Empire,

governed by Aetius, and the Franks under the successors of Clodion, there was

either open war or a hollow truce. The succession to the chief power in the

Salian tribe was the subject of a violent dispute between two Frankish princes,

the elder of whom is supposed by some to have been called Merovaeus. We have seen reason

to doubt the existence of a prince of this name; and there is no evidence that

either of the rival candidates was a son of Clodion. Whatever their parentage

or name may have been, the one took part with Attila, and the other with the Roman

Aetius, on condition, no doubt, of having their respective claims allowed and

supported by their allies. In the bloody and decisive battle of the Catalaunian Fields round

Châlons, Franks, under the name of Leti and Ripuarii, served under the

so-called Merovaeus in

the army of Aetius, together with Theoderic and

his Visigoths. Among the forces of Attila another body of Franks was arrayed,

either by compulsion, or instigated to this unnatural course by the fierce

hatred of party spirit. From the result of the battle of Châlons, we must

suppose that the ally of Aetius succeeded to the throne of Clodion.

The

effects of the invasion of Gaul by Attila were neither great nor lasting, and

his retreat left the German and Roman parties in much the same condition as he

found them. The Roman Empire indeed was at an end in that province, yet the

valor and wisdom of Egidius enabled him to maintain,

as an independent chief, the authority which he had faithfully exercised, as

Master-General of Gaul, under the noble and virtuous Magorian.

The extent of his territory is not clearly defined, but it must have been, in

part at least, identical with that of which his son and successor, Syagrius,

was deprived by Clovis. Common opinion limits this to the country between the

Oise, the Marne, and the Seine, to which some writers have added Auxerre and

Troyes. The respect in which Egidius was held by the

Franks, as well as his own countrymen, enabled him to set at defiance the

threats and machinations of the barbarian Ricimer, who virtually ruled at Rome,

though in another's name. The strongest proof of the high opinion they

entertained of the merits of Egidius, is said to have

been given by the Salians in the reign of their next king. The prince, to whom

the name Merovaeus has been arbitrarily assigned, was

succeeded by his son Childeric, in ad 456. The conduct of this licentious youth

was such as to disgust and alienate his subjects, who had not yet ceased to

value female honor, nor adopted the loose manners of the Romans and their

Gallic imitators. The authority of the Salian kings over the fierce warriors of

their tribe was held by a precarious tenure. The loyalty which distinguished

the Franks in later times had not yet arisen in their minds, and they did not

scruple to send the corrupter of their wives and daughters into ignominious

exile. Childeric took refuge with Bissinus(or Bassinus), king of the Thuringians, a people dwelling on

the river Unstrut. It was then that the Franks,

according to the somewhat improbable account of Gregory, unanimously chose Egidius for their king, and actually submitted to his rule

for the space of eight years. At the end of that period, returning affection

for their native prince, the mere love of change, or the machinations of a

party, induced the Franks to recall Childeric from exile, or, at all events, to

allow him to return. Whatever may have been the cause of his restoration, it

does not appear to have been the consequence of an improvement in his morals.

The period of his exile had been characteristically employed in the seduction

of Basina, the wife of his hospitable protector at the Thuringian Court. This

royal lady, whose character may perhaps do something to diminish the guilt of

Childeric in our eyes, was unwilling to be left behind on the restoration of

her lover to his native country. Scarcely had he re-established his authority

when he was unexpectedly followed by Basina, whom he immediately married. The

offspring of this questionable alliance was Clovis, who was born in the year

466. The remainder of Childeric’s reign was chiefly spent in a struggle with

the Visigoths, in which Franks and Romans, under their respective leaders,

Childeric and Egidius, were amicably united against

the common foe.

“THE ELDEST SON OF THE CHURCH” - DIVISIONS OF GAUL.

We hasten

to the reign of Clovis, who, during a rule of about thirty years, not only

united the various tribes of Franks under one powerful dynasty, and founded a

kingdom in Gaul on a broad and enduring basis, but made his throne the centre of union to by far the greater portion of the whole

German race.

When

Clovis succeeded his father as king of the Salians, at the early age of

fifteen, the extent of his territory and the number of his subjects were, as we

know, extremely small; at his death, he left to his successors a kingdom more

extensive than that of modern France.

The

influence of the grateful partiality discernible in the works of Catholic

historians and chroniclers towards “the Eldest Son of the Church”, who secured

for them the victory over heathens on the one side, and heretics on the other,

prevents us from looking to them for an unbiassed estimate

of his character. Many of his crimes appeared to be committed in the cause of

Catholicity itself, and these they could hardly see in their proper light.

Pagans and Arians would have painted him in different colors; and had any of

their works come down to us, we might have sought the truth between the

positive of partiality and the negative of hatred. But fortunately, while the

chroniclers praise his actions in the highest terms, they tell us what those

actions were, and thus compel us to form a very different judgment from their

own. It would not be easy to extract from the pages of his greatest admirers

the slightest evidence of his possessing any qualities but those which are

necessary to a conqueror. In the hands of Providence he was an instrument of

the greatest good to the country he subdued, inasmuch as he freed it from the

curse of division into petty states, and furthered the spread of Christianity

in the very heart of Europe. But of any word or action that could make us

admire or love the man, there is not a single trace in history. His undeniable

courage is debased by a degree of cruelty unusual even in his times; and the

consummate skill and prudence, which did more to raise him to his high position

than even his military qualities, are rendered odious by the forms they take of

unscrupulous falsehood, meanness, cunning and hypocrisy.

It will

add to the perspicuity of our brief narrative of the conquests of Clovis, if we

pause for a moment to consider the extent and situation of the different

portions into which Gaul was divided at his accession.

There

were in all six independent states: 1st, that of the Salians; 2nd, that of the

Ripuarians; 3rd, that of the Visigoths; 4th, that of the Burgundians; 5th, the

kingdom of Syagrius; and, 6th, Armorica (by which the whole sea-coast between

Seine and Loire was then signified). Of the two first we have already spoken.

The Visigoths held the whole of Southern Gaul. Their boundary to the north was

the river Loire, and to the east the Pagus Vellavus (Auvergne).

The

boundary of the Burgundians on the side of Roman Gaul, was the Pagus Lingonicus (Upper Marne); to the west they

were bounded by the territory of the Visigoths, as above described.

The

territory still held by the Romans was divided into two parts, of which the one

was held by Syagrius, who, according to common opinion, only ruled the country

between Oise, Marne, and Seine; to this some writers have added Auxerre,

Troyes, and Orleans. The other — viz., that portion of Roman Gaul not subject

to Syagrius—is of uncertain extent. Armorica (Bretagne and Maine), was an

independent state, inhabited by Britons and Saxons; but what was its form of

government is not exactly known. It is important to bear these geographical

divisions in mind, because they coincide with the successive Frankish conquests

made under Clovis and his sons.

CLOVIS ATTACKS SYAGRIUS.

It would

be unphilosophical to ascribe to Clovis a

preconceived plan of making himself master of these several independent states,

and of not only overthrowing the sole remaining pillar of the Roman Empire in

Gaul, but, what was far more difficult, of subduing other German tribes, as

fierce and independent, and in some cases more numerous than his own. In what

he did, he was merely gratifying a passion for the excitements of war and

acquisition, and that desire of expanding itself to its utmost limits, which is

natural to every active, powerful, and imperious mind. He must indeed have

been more than human to foresee, through all the obstacles that lay in his

path, the career he was destined by Providence to run. He was not even master

of the whole Salian tribe; and besides the Salians, there were other Franks on

the Rhine, the Scheldt, the Meuse, and the Moselle,

in no way inferior to his own subjects, and governed by kings of the same

family as himself. Nor was Syagrius, to whom the anomalous power of his father Egidius had descended, a despicable foe. His merits,

indeed, were rather those of an able lawyer and a righteous judge than of a

warrior; but he had acquired by his civil virtues a reputation which made him

an object of envy to Clovis, who dreaded perhaps the permanent establishment of

a Roman dynasty in Gaul. There were reasons for attacking Syagrius first, which

can hardly have escaped the cunning of Clovis, and which doubtless guided him

in the choice of his earliest victim. The very integrity of the noble Roman’s

character was one of these reasons. Had Clovis commenced the work of

destruction by attacking his kinsmen Sigebert of Cologne and Ragnachar of Cambrai, he would not only have received no

aid from Syagrius in his unrighteous aggression, but might have found him ready

to oppose it. But against Syagrius it was easy for Clovis to excite the

national spirit of his brother Franks, both in and out of his own territory. In

such an expedition, even had the kings declined to take an active part, he

might reckon on crowds of volunteers from every Frankish gau.

As soon

therefore as he had emerged from the forced inactivity of extreme youth (a

period in which, fortunately for him, he was left undisturbed by his less

grasping and unscrupulous neighbors), he determined to bring the question of

pre-eminence between the Franks and Romans to as early an issue as possible.

Without waiting for a plausible ground of quarrel, he challenged Syagrius,

more Germanico, to

the field, that their respective fates might be determined by the God of

Battles. Ragnachar of Cambrai was solicited to

accompany his treacherous relative on this expedition, and agreed to do

so. Ghararich,

another Frankish prince, whose alliance had been looked for, preferred waiting

until fortune had decided, with the prudent intention of siding with the

winner, and coming fresh into the field in time to spoil the vanquished.

Syagrius

was at Soissons, which he had inherited from his father, when Clovis, with

characteristic decision and rapidity, passed through the wood of Ardennes, and

fell upon him with resistless force. The Roman was completely defeated, and the

victor, having taken possession of Soissons, Rheims, and other Roman towns in

the Belgica Secunda,

extended his frontier to the river Loire, the boundary of the Visigoths. This

battle took place in ad 486.

We know

little or nothing of the materials of which the Roman army was composed. If it

consisted entirely of Gauls, accustomed to depend on Roman aid, and destitute

of the spirit of freemen, the ease with which Syagrius was defeated will cause

us less surprise. Having lost all in a single battle, the unfortunate Roman

fled for refuge to Toulouse, the court of Alaric, king of the Visigoths, who

basely yielded him to the threats of the youthful conqueror. But one fate

awaited those who stood in the way of Clovis: Syagrius was immediately put to

death, less in anger, than from the calculating policy which guided all the

movements of the Salian’s unfeeling heart.

During

the next ten years after the death of Syagrius, there is less to relate of

Clovis than might be expected from the commencement of his career. We cannot

suppose that such a spirit was really at rest: he was probably nursing his

strength, and watching his opportunities; for, with all his impetuosity, he was

not a man to engage in an undertaking without good assurance of success.

Almost

the only expedition of this inactive period of his life, is one recorded in a

doubtful passage by Gregory of Tours, as having been made against the Tongrians. This people lived in

the ancient country of the Eburones, on the

Elbe, and had formerly been subjects of his mother Basina.

The Tongrians were

defeated, and their territory was, nominally at least, incorporated with the

kingdom of Clovis.

ALEMANNI DEFEATED AT ZÜLPICH - CONVERSION OF CLOVIS.

In the

year 496 A.D. the Salians began that career of

conquest, which they followed up with scarcely any intermission until the death

of their warrior king.

The

Alemanni, extending themselves from their original seats on the right bank of

the Rhine, between the Main and the Danube, had pushed forward into Germanica Prima, where they came into collision with

the Frankish subjects of King Sigebert of Cologne. Clovis flew to the assistance

of his kinsman, and defeated the Alemanni in a great battle in the neighborhood

of Zülpich. He then established a considerable number

of his Franks in the territory of the Alamanni,

the traces of whose residence are found in the names of Franconia and Frankfort.

The same

year is rendered remarkable in ecclesiastical history by the conversion of

Clovis to Christianity. In AD 493, he had married Clothildis, Chilperic the king of Burgundy’s daughter, who, being herself a Christian, was naturally

anxious to turn away her warlike spouse from the rude faith of his forefathers.

The real result of her endeavors it is impossible to estimate, but, at all

events, she has not received from history the credit of success. The mere

suggestions of an affectionate wife would be considered as too simple and

prosaic a means of accounting for a change involving such mighty consequences.

The conversion of Clovis was so vitally important to the interests of the

Catholic Church, that the chroniclers of that wonder-loving age, profuse in the

employment of extraordinary means for the smallest ends, could never be brought

to believe that this great event was the result of anything but a miracle of

the most public and striking character.

The way

in which the convictions of Clovis were changed is unknown to us, but there

were natural agencies at work, and his conversion is not, under the

circumstances, a thing to excite surprise. According to the common belief,

however, in the Roman Church, it was in the battle of Zülpich that the heart of Clovis, callous to the pious solicitude of his wife, and the

powerful and alluring influence of the catholic ritual, was touched by a

special interposition of Providence in his behalf. When the fortune of the

battle seemed turning against him, he thought of the God whom his wife adored,

of whose power and majesty he had heard so much, and vowed that if he escaped

the present danger, and came off victorious, he would suffer himself to be

baptized, and become the champion of the Christian Faith. Like another

Constantine, he saw written on the face of Heaven that his prayer was heard; he

conquered, and fulfilled his promise at Christmas in the same year, when Remigius at Rheims, with three thousand of his

followers.

The

sincerity of Clovis’s conversion has been called in

question for many reasons, such as the unsuit ability of his subsequent life to

Christian principles, but chiefly on the ground of the many political

advantages to be derived from a public profession of the Catholic Faith. We are

too ready with such explanations of the actions of distinguished characters,

too apt to forget that politicians are also men, and to overlook the very

powerful influences which lie nearer to their hearts than even political

calculation. A spirit was abroad in the world, drawing men away from the graves

of a dead faith to the life and light of the Gospel, a spirit which not even

the coldest and sternest heart could altogether resist. There was something,

too, peculiarly imposing in the attitude of the Christian Church at that

period. All else in the Roman world seemed dying of mere weakness and old

age—the Christian Church was still in the vigour of

youth, and its professors were animated by indomitable perseverance and

boundless zeal. All else fell down in terror before the Barbarian conqueror—the

fabric of the Church seemed indestructible, and its ministers stood erect in

his presence, as if depending for strength and aid upon a power, which was the

more terrible, because indefinite in its nature and uncertain in its mode of

operation.

Nor were

there wanting to the Catholic Church, even at that stage of its development,

those external means of influence which tell with peculiar force upon the

barbarous and untutored mind. The emperors of the Roman world had reared its

temples, adorned its shrines, and regulated its services, in a manner which

seemed to them best suited to the majesty of Heaven and their own. Its altars

were served by men distinguished by their learning, and by that indestructible

dignity of deportment, which is derived from conscious superiority. The praises

of God were chanted forth in well-chosen words and impressive tones, or sung in

lofty strains by tutored voices; while incense rose to the vaulted aisle, as if

to bear the prayers of the kneeling multitude to the very gates of Paradise.

And

Clovis was as likely to be worked upon by such means as the meanest of his

followers. We must not suppose that the discrepancy between his Christian

profession and his public and private actions, which we discern so clearly, was

equally evident to himself. How should it be so? His own conscience was not

specially enlightened beyond the measure of his age. The bravest warriors of

his nation hailed him as a patriot and hero, and the ministers of God assured

him that his victories were won in the service of Truth and Heaven. It is

always dangerous to judge of the sincerity of men’s religious—perhaps we should

say theological—convictions by the tenor of their moral conduct, and this even

in our own age and nation; but far more so in respect to men of other times and

countries, at a different stage of civilization and religious development, at

which the scale of morality was not only lower, but differently graduated from

our own.

The

conscience of a Clovis remained undisturbed in the midst of deeds whose

enormity makes us shudder; and, on the other band, how trivial in our eyes are

some of those offences which loaded him with the heaviest sense of guilt! The

eternal laws of the God of justice and mercy might be broken with impunity; and

what we should call the basest treachery and the most odious cruelty, employed

to compass the destruction of an heretical or pagan enemy; but woe to him who

offended St. Martin, or laid a finger on the property of the meanest of his

servants! When Clovis was seeking to gratify his lust of power, he believed, no

doubt, that he was at the same time fighting under the banner of Christ, and

destroying the enemies of God. And no wonder, for many a priest and bishop

thought the same, and told him what they thought.

We are,

however, far from affirming that the political advantages to be gained from an

open avowal of the Catholic Faith at this juncture escaped the notice of so

astute a mind as that of Clovis. No one was more sensible of those advantages

than he was. The immediate consequences were indeed apparently disastrous. He

was himself fearful of the effect which his change of religion might have upon

his Franks, and we are told that many of them left him and joined his

kinsman Ragnarich.

But the ill effects, though immediate, were slight and transient, while the

good results went on accumulating from year to year. In the first place, his

baptism into the Catholic Church conciliated for him the zealous affection of

his Gallo-Roman subjects, whose number and wealth, and, above all, whose

superior knowledge and intelligence, rendered their aid of the utmost value.

With respect to his own Franks, we are justified in supposing that, removed as

they were from the sacred localities with which their faith was intimately

connected, they either viewed the change with indifference, or, wavering

between old associations and present influences, needed only the example of the

king to decide their choice, and induce them to enlist under the banner of the

Cross.

The

German neighbors of Clovis had either preserved their ancient faith or adopted

the Arian heresy. His conversion therefore was advantageous or disadvantageous

to him, as regarded them, according to the objects he had in view. Had he

really desired to live with his compatriot kings on terms of equality and

friendship, his reception into a hostile Church would certainly not have

furthered his views. But nothing was more foreign to his thoughts than

friendship and alliance with any of the neighboring tribes. His desire was to

reduce them all to a state of subjection to himself. He had the genuine spirit

of the conqueror, which cannot brook the sight of independence; and his keen

intellect and unflinching boldness enabled him to see his advantages and to turn

them to the best account.

Even in

those countries in which Heathenism or Arian Christianity prevailed, there was

generally a zealous and united community of Catholic Christians (including all

the Romance inhabitants), who, being outnumbered and sometimes persecuted, were

inclined to look for aid abroad. Clovis became by his conversion the object of

hope and attachment to such a party in almost every country on the continent of

Europe. He had the powerful support of the whole body of the Catholic clergy, in

whose hearts the interests of their Church far outweighed all other

considerations. In other times and lands (in our own for instance) the spirit

of loyalty and the love of country have often sufficed to counteract the

influence of theological opinions, and have made men patriots in the hour of

trial, when their spiritual allegiance to an alien head tempted them to be

traitors. But what patriotism could Gallo-Romans feel, who for ages had been

the slaves of slaves? or what loyalty to barbarian oppressors, whom they

despised as well as feared?

The happy

effects of Clovis’s conversion were not long in

showing themselves. In the very next year after that event (AD 497) the Armoricans, inhabiting the country between the Seine and

Loire, who had stoutly defended themselves against the heathen Franks,

submitted with the utmost readiness to the royal convert whom bishops delighted

to honor; and in almost every succeeding struggle the advantages he derived

from the strenuous support of the Catholic party become more and more clearly

evident.

STRUGGLE WITH THE VISIGOTHS - BATTLE OF VOUGLÉ

In ad 500

Clovis reduced the Burgundians to a state of semi-dependence, after a fierce

and bloody battle with Gundobald, their king, at

Dijon on the Ousche.

In this conflict, as in almost every other, Clovis attained his ends in a great

measure by turning to account the dissensions of his enemies. Gundobald had called upon his brother Godegisil, who ruled over one

division of their tribe, to aid him in repelling the attack of the Franks. The

call was answered, in appearance at least; but in the decisive struggle Godegisil, according to a secret

understanding, deserted with all his forces to the enemy. Gundobald was of course defeated, and submitted to conditions which, however galling to

his pride and patriotism, could not have been very severe, since we find him

immediately afterwards punishing the treachery of his brother, whom be besieged

in the city of Vienne, and put to death in an Arian Church.

The circumstances

of the times, rather than the moderation of Clovis, prevented him from calling Gundobald to account. A far more arduous struggle was at

hand, which needed all the wily Salian’s resources

of power and policy to bring to a successful issue—the struggle with the

powerful king and people of the Visigoths, whose immediate neighbor he had

become after the voluntary submission of the Armoricans in

AD497. The valor and conduct of their renowned king Euric had put the Western

Goths in full possession of all that portion of Gaul which lay between the

rivers Loire and Rhone, together with nearly the whole of Spain. That

distinguished monarch had lately been succeeded by his son Alaric II, who was

now in the flower of youth. It was in the war with this ill-starred prince—the

most difficult and doubtful in which he had been engaged—that Clovis

experienced the full advantages of his recent change of faith. King Euric, who

was an Arian, wise and great as he appears to have been in many respects, had

alienated the affections of multitudes of his people by persecuting the

Catholic minority; and though the same charge does not appear to lie against

Alaric, it is evident that the hearts of his orthodox subjects beat with no

true allegiance towards their heretical king. The baptism of Clovis had turned

their eyes towards him, as one who would not only free them from the

persecution of their theological enemies, but procure for them and their Church

a speedy victory and a secure predominance. The hopes they had formed, and the

aid they were ready to afford him, were not unknown to Clovis, whose eager

rapacity was only checked by the consideration of the part which his

brother-in-law Theoderic,

King of the Ostrogoths, was likely to take in the matter. This great and

enlightened Goth, whose refined magnificence renders the contemptuous sense in

which we use the term Gothic more than usually inappropriate, was ever ready to

mediate between kindred tribes of Germans, whom on every suitable occasion he

exhorted to live in unity, mindful of their common origin. He is said on this

occasion to have brought about a meeting between Clovis and Alaric on a small

island in the Loire in the neighborhood of Amboise. The story is very doubtful,

to say the least. Had he done so much, he would probably have done more, and

have shielded his youthful kinsman with his strong right arm. Whatever he did

was done in vain. The Frankish conqueror knew his own advantages and determined

to use them to the utmost. He received the aid not only of his kinsman Sigebert

of Cologne, who sent an army to his support under Ghararich, but of the king of the Burgundians, who

was also a Catholic. With an army thus united by a common faith, inspired by

religious zeal, and no less so by the Frankish love of booty, Clovis marched to

almost certain victory over an inexperienced leader and a kingdom divided

against itself.

It is

evident from the language of Gregory of Tours, that this conflict between the

Franks and Visigoths was regarded by the orthodox party of his own and

preceding ages as a religious war, on which, humanly speaking, the prevalence

of the Catholic or the Arian creed in Western Europe depended. Clovis did

everything in his power to deepen this impression. He could not, he said,

endure the thought that “those Arians” held a part of his beautiful Gaul. As he

passed through the territory of Tours, which was supposed to be under the

peculiar protection of St. Martin, he was careful to preserve the strictest

discipline among his soldiers, that he might further conciliate the Church and

sanctify his undertaking. On his arrival at the city of Tours, he publicly

displayed his reverence for the patron saint, and received the thanks and good

wishes of a whole chorus of priests assembled in St. Martin’s Church. He was

guided (according to one of the legends by which his progress has been so

profusely adorned) through the swollen waters of the river Vienne by “a hind of wonderful magnitude”; and, as he approached

the city of Poitiers, a pillar of fire (whose origin we may trace, as suits our

views, to the favor of heaven or the treachery of man) shone forth from the

cathedral, to give him the assurance of success, and to throw light upon his

nocturnal march. The Catholic bishops in the kingdom of Alaric were universally

favorable to the cause of Clovis, and several of them, who had not the patience

to postpone the manifestation of their sympathies, were expelled by Alaric from

their sees. The majority indeed made a virtue of necessity, and prayed

continually and loudly, if not sincerely, for their lawful monarch. Perhaps

they had even in that age learned to appreciate the efficacy of mental

reservation.

Conscious

of his own weakness, Alaric retired before his terrible and implacable foe, in

the vain hope of receiving assistance from the Ostrogoths. He halted at last in

the plains of Vouglé,

behind Poitiers, but even then rather in compliance with the wishes of his

soldiers than from his own deliberate judgment. His soldiers, drawn from a

generation as yet unacquainted with war, and full of that overweening

confidence which results from inexperience, were eager to meet the enemy.

Treachery, also, was at work to prevent him from adopting the only means of

safety, which lay in deferring as long as possible the too unequal contest. The

Franks came on with their usual impetuosity, and with a well-founded confidence

in their own prowess; and the issue of the battle was in accordance with the

auspices on either side. Clovis, no less strenuous in actual fight than wise

and cunning in council, exposed himself to every danger, and fought hand to

hand with Alaric himself. Yet the latter was not slain in the field, but in the

disorderly flight into which the Goths were quickly driven. The victorious

Franks pursued them as far as Bordeaux, where Clovis passed the winter, while

Theodoric, his son, was overrunning Auvergne, Quincy, and Rovergne. The Goths, whose new

king was a minor, made no further resistance; and in the following year the

Salian chief took possession of the royal treasure at Toulouse. He also took

the town of Angouleme, at the capture of which he was doubly rewarded for his

services to the Church, for not only did the inhabitants of that place rise in

his favor against the Visigothic garrison, but the very walls, like those of

Jericho, fell down at his approach!

AD 508.

A short

time after these events, Clovis received the titles and dignity of Roman Patricius and Consul from the Greek Emperor Anastasius; who

appears to have been prompted to this act more by motives of jealousy and

hatred towards Theodoric the Ostrogoth, than by any love he bore the restless

and encroaching Frank. The meaning of these obsolete titles, as applied to

those who stood in no direct relation to either division of the Roman Empire,

has never been sufficiently explained. We are at first surprised that

successful warriors and powerful kings like Clovis, Pepin, and Charlemagne

himself, should condescend to accept such empty honors at the hands of the

miserable eunuch-ridden monarchs of the East. That the Byzantine Emperors

should affect a superiority over contemporary sovereigns is intelligible

enough; the weakest idiot among them, who lived at the mercy of his women and

his slaves, had never resigned one title of his pretensions to that universal

empire which an Augustus and a Trajan once possessed. But whence the

acquiescence of Clovis and his great successors in this arrogant assumption? We

may best account for it by remarking how long the prestige of power survives

the strength that gave it. The sun of Rome was set, but the twilight of her

greatness still rested on the world. The German kings and warriors received

with pleasure, and wore with pride, a title which brought them into connection

with that imperial city, of whose universal dominion, of whose skill in arms

and arts, the traces lay everywhere around them.

Nor was

it without some solid advantages in the circumstances in which Clovis was

placed. He ruled over a vast population, which had not long ceased to be

subjects of the Empire, and still rejoiced in the Roman name. He fully

appreciated their intellectual superiority, and had already experienced the

value of their assistance. Whatever, therefore, tended to increase his personal

dignity in their eyes (and no doubt the solemn proclamation of his Roman titles

had this tendency) was rightly deemed by him of no small importance.

In the

same year that he was invested with the diadem and purple robe in the church of

St. Martin at Tours the encroaching Franks had the southern and eastern limits

of their kingdom marked out for them by the powerful hand of Theodoric the

Great. The brave but peace-loving Goth had trusted too much to his influence

with Clovis, and had hoped to the last to save the unhappy Alaric, by warning

and mediation. The slaughter of the Visigoths, the death of Alaric himself, the

fall of Angouleme and Toulouse, the advance of the Franks upon the Rhone, where

they were now besieging Arles, had effectually undeceived him. He now prepared

to bring forward the only arguments to which the ear of a Clovis is ever open,

the battle-cry of a superior army. His faithful Ostrogoths were summoned to

meet in the month of June, ad 508, and he placed a powerful army under the

command of Eva (Ibba or Hebba), who led his forces into

Gaul over the southern Alps. The Franks and Burgundians, who were investing

Arles and Carcassonne, raised the siege and retired, but whether without or in

consequence of a battle, is rendered doubtful by the conflicting testimony of

the annalists. The subsequent territorial position

of the combatants, however, favors the account that a battle did take place, in

which Clovis and his allies received a most decided and bloody defeat.

The check

thus given to the extension of his kingdom at the expense of other German

nations, and the desire perhaps of collecting fresh strength for a more

successful struggle hereafter, seem to have induced Clovis to turn his

attention to the destruction of his Merovingian kindred. The manner in which he

effected his purpose is related with a fullness which naturally excites

suspicion. But though it is easy to detect both absurdity and inconsistency in

many of the romantic details with which Gregory has furnished us, we see no

reason to deny to his statements a foundation of historical truth.

CLOVIS AND HIS KINSMEN.

Clovis

was still but one of several Frankish kings; and of these Sigebert of Cologne,

king of the Ripuarians, was little inferior to him in the extent of his

dominions and the number of his subjects. But in other respects—in mental

activity and bodily prowess—“the lame” Sigebert was no match for his Salian

brother. The other Frankish rulers were, Chararich,

of whom mention has been made in connection with Syagrius, and Ragnachar (or Ragnachas),

who held his court at Cambrai. The kingdom of Sigebert extended along both

banks of the Rhine, from Mayence down to Cologne; to

the west along the Moselle as far as

Treves; and on the east to the river Fulda and the borders of Thuringia. The

Franks who occupied this country are supposed to have taken possession of it in

the reign of Valentinian III, when Mayence, Cologne,

and Treves, were conquered by a host of Ripuarians. Sigebert, as we have seen,

had come to the aid of Clovis, in two very important battles with the Alemanni

and the Visigoths, and had shown himself a ready and faithful friend whenever

his co-operation was required. But gratitude was not included among the graces

of the champion of Catholicity, who only waited for a suitable opportunity to

deprive his ally of throne and life. The present juncture was favorable to his

wishes, and enabled him to rid himself of his benefactor in a manner peculiarly

suited to his taste. An attempt to conquer the kingdom of Cologne by force of

arms would have been but feebly seconded by his own subjects, and would have

met with a stout resistance from the Ripuarians, who were conscious of no

inferiority to the Salian tribe. His efforts were therefore directed to the

destruction of the royal house, the downfall of which was hastened by internal

divisions. Clotaire (or Clotarich),

the expectant heir of Sigebert, weary of hope deferred, gave a ready ear to the

hellish suggestions of Clovis, who urged him, by the strongest appeals to his

ambition and cupidity, to the murder of his father. Sigebert was slain by his

own son in the Buchonian Forest

near Fulda. The wretched parricide endeavored to secure the further connivance

of his tempter, by offering him a share of the blood-stained treasure he had

acquired. But Clovis, whose part in the transaction was probably unknown,

affected a feeling of horror at the unnatural crime, and procured the immediate

assassination of Clotaire; an act which rid him of a rival, silenced an

embarrassing accomplice, and tended rather to raise than to lower him in the

opinion of the Ripuarians. It is not surprising, therefore, that when Clovis

proposed himself as the successor of Sigebert, and promised the full

recognition of all existing rights, his offer should be joyfully accepted. In

ad 509 he was elected king by the Ripuarians, and raised upon a shield in the

city of Cologne, according to the Frankish custom, amid general acclamation.

“And

thus”, says Gregory of Tours, in the same chapter in which he relates the

twofold murder of his kindred, “God daily prostrated his enemies before him and

increased his kingdom, because he walked before him with an upright heart, and

did what was pleasing in his eyes!”—so completely did his services to the

Catholic Church conceal his moral deformities from the eyes of even the best of

the ecclesiastical historians.

To the

destruction of his next victim, Chararich, whose

power was far less formidable than that of Sigebert, he was impelled by

vengeance as well as ambition. That cautious prince, instead of joining the

other Franks in their attack upon Syagrius, had stood aloof and waited upon

fortune. Yet we can hardly attribute the conduct of Clovis towards him chiefly

to revenge, for his most faithful ally had been his earliest victim; and friend

and foe were alike to him, if they did but cross the path of his ambition.

After getting possession of Chararich and his son, by

tampering with their followers, Clovis compelled them to cut off their royal

locks and become priests; subsequently, however, he caused them to be put to

death.

Ragnachar of Cambrai, whose kingdom

lay to the north of the Somme, and extended through Flanders and Artois, might

have proved a more formidable antagonist, had he not become unpopular among his

own subjects by the disgusting licentiousness of his manners. The account which

Gregory gives of the manner in which his ruin was effected is more curious than

credible, and adds the charge of swindling to the black list of crimes recorded

against the man who “walked before God with an upright heart”. According to the

historian, Clovis bribed the followers of Ragnachar with armour of gilded iron, which they mistook, as he

intended they should, for gold. Having thus crippled by treachery the strength

of his enemy, Clovis led an army over the Somme, for the purpose of attacking

him in his own territory. Ragnachar prepared to meet

him, but was betrayed by his own soldiers and delivered into the hands of the

invader. Clovis, with facetious cruelty, reproached the fallen monarch for

having disgraced their common family by suffering himself to be bound, and then

split his skull with an axe. The same absurd charge was brought against Richar, the brother of Ragnachar, and the same punishment inflicted on him. A

third brother was put to death at Mans

Gregory

refers, though not by name, to other kings of the same family, who were all

destroyed by Clovis. “Having killed many other kings”, he says, “who were his

kinsmen, because he feared they might deprive him of his power, he extended his

kingdom through the whole of Gaul”. He also tells us that the royal hypocrite,

having summoned a general assembly, complained before it, with tears in his

eyes, that he was “alone in the world”. “Alas, for me!” he said, “I am left as

an alien among strangers, and have no relations who can assist me”. This he did,

according to Gregory, “not from any real love of his kindred, or from remorse

at the thought of his crimes, but that he might find out any more relations and

put them also to death”.

Clovis

died at Paris, in AD 511, in the forty-fifth year of his age and the

thirtieth of his active, bloodstained, and eventful reign. He lived therefore

only five years after the decisive battle of Vouglé.

Did we

not know, from the judgment he passes on other characters in his history, that

Gregory of Tours was capable of appreciating the nobler and gentler qualities

of our nature, we might easily imagine, as we read what he says of Clovis,

that, Christian bishop as he was, he had an altogether different standard of

right and wrong from ourselves. Not a single virtuous or generous action has

the panegyrist found to record of his favored hero, while all that he does

relate of him tends to deepen our conviction that this favorite of Heaven, in

whose behalf miracles were freely worked, whom departed saints led on to

victory, and living ministers of God delighted to honor, was quite a phenomenon

of evil in the moral world, from his combining in himself the opposite and

apparently incompatible vices of the meanest treachery, and the most audacious

wickedness.

HIS

SERVICES TO CHURCH AND STATE.

We can

only account for this amazing obliquity of moral vision in such a man as

Gregory, by ascribing it to the extraordinary value attached in those times

(and would that we could say in those times only) to external acts of devotion,

and to every service rendered to the Roman Church. If, in far happier ages than

those of which we speak, the most polluted consciences have purchased

consolation and even hope, by building churches, endowing monasteries, and

paying reverential homage to the dispensers of God’s mercy, can we wonder that

the extraordinary services of a Clovis to Catholic Christianity should cover

even his foul sins as with a cloak of snow?

He had,

indeed, without the slightest provocation, deprived a noble and peaceable

neighbor of his power and life. He had treacherously murdered his royal

kindred, and deprived their children of their birthright. He had on all

occasions shown himself the heartless ruffian, the greedy conqueror, the bloodthirsty

tyrant; but by his conversion he had led the Roman Church from the Scylla

and Charybdis of Heresy and Paganism,

planted it on a rock in the very centre of Europe,

and fixed its doctrines and traditions in the hearts of the conquerors of the

West.

Other

reasons, again, may serve to reconcile the politician to his memory. The

importance of the task which he performed (though from the basest motives), and

the influence of his reign on the destinies of Europe can hardly be overrated.

He founded the monarchy on a firm and enduring basis. He leveled, with a strong

though bloody hand, the barriers which separated Franks from Franks, and

consolidated a number of isolated and hostile tribes into a powerful and united

nation. It is true, indeed, that this unity was soon disturbed by divisions of

a different nature; yet the idea of its feasibility and desirableness was

deeply fixed in the national mind; a return to it was often aimed at, and

sometimes accomplished.

II.

FROM THE DEATH OF CLOVIS TO

THE DEATH OF CLOTHAIRE I

AD 511—561.

There can

be no stronger evidence of the strength and consistency which the royal

authority had attained in the hands of Clovis, than the peaceful and undisputed

succession of his sons to the vacant throne. It would derogate from our opinion

of the political sagacity of Clovis, were we to attribute to his personal

wishes the partition of his kingdom among his four sons. We have no account,

moreover, of any testamentary dispositions made by him to this effect, and are

justified in concluding that the division took place in accordance with the

general laws of inheritance which then prevailed among the Germans. However

clearly he may have foreseen the disastrous consequences of destroying the

unity which it had been one object of his life to effect, his posthumous

influence would hardly have sufficed to reconcile his younger sons to their own

exclusion, supported as they would naturally be by the national sympathy in

the unusual hardship of their lot.

Of the

four sons of Clovis, Theoderic (Dietrich,

Thierry), Clodomir,

Childebert, and Clotar (Clotaire),

the eldest, who was then probably about twenty-four years of age, was the son

of an unknown mother, and the rest, the offspring of the Burgundian princess

Clotilda. The first use they made of the royal power which had descended to

them was to divide the empire into four parts; in which division, though

Gregory describes them as sharing ‘aequa lance’,

the eldest son appears to have had the lion’s share. We should in vain endeavor